By: Rudraksh Saklani, Research Analyst, GSDN

In this era, which is not of war, but of geo-economics rather, the latent nature and unmet potential of the South American continent have begun to witness realignment within the broader rules-based global order. As the intra-nation as well as inter-nation power dynamics shift, in order to not repeat the mistakes of the past, it is only fair to not underestimate the impact and capability of the nations that make up this continent. It is equally imperative to let go of and overcome the stereotypes that engulf the image South America holds in the eyes of rest of the world, often restricted to its football prowess, Iberian colonial past, oil reserves, infamous drug cartels and a unifying hero in the form and resilient spirit of Simón Bolívar.

Introductory Perspective

South America, often mistaken to be on the periphery, is actually central to the global discourse and logistical realities pertaining to food, energy, and climate security. Amidst rising great power competition between the United States of America (USA) and China. South America most definitely matters geopolitically because of its multi-layered dynamism as a continent.

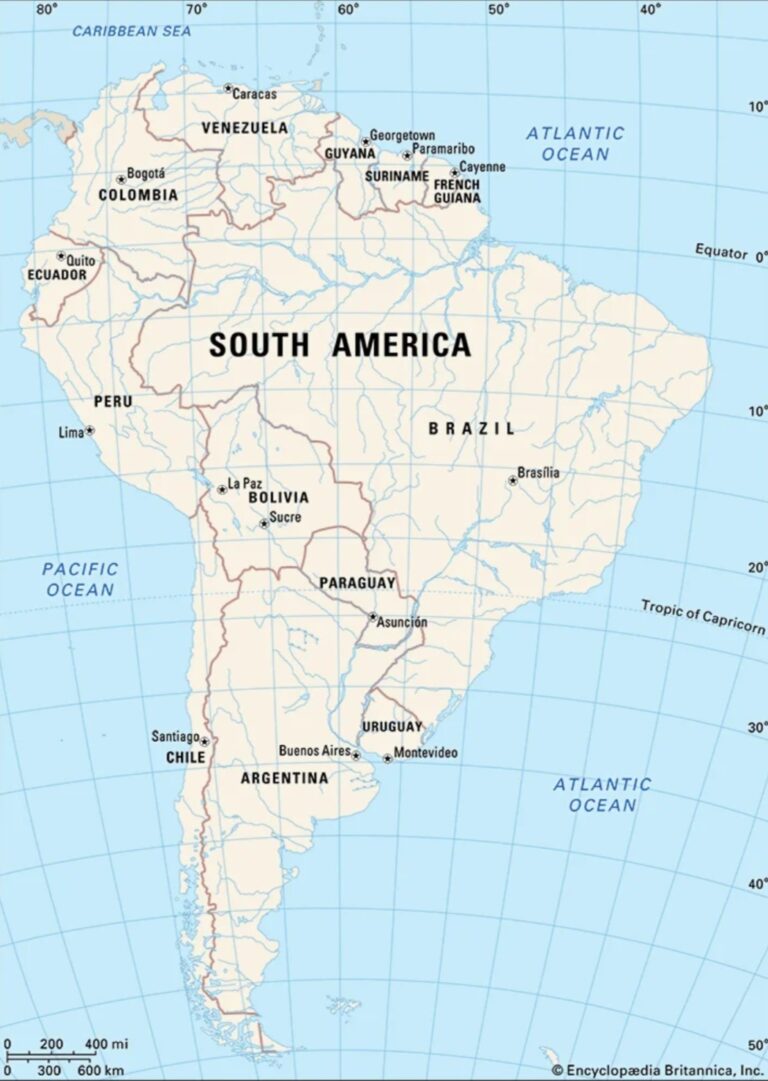

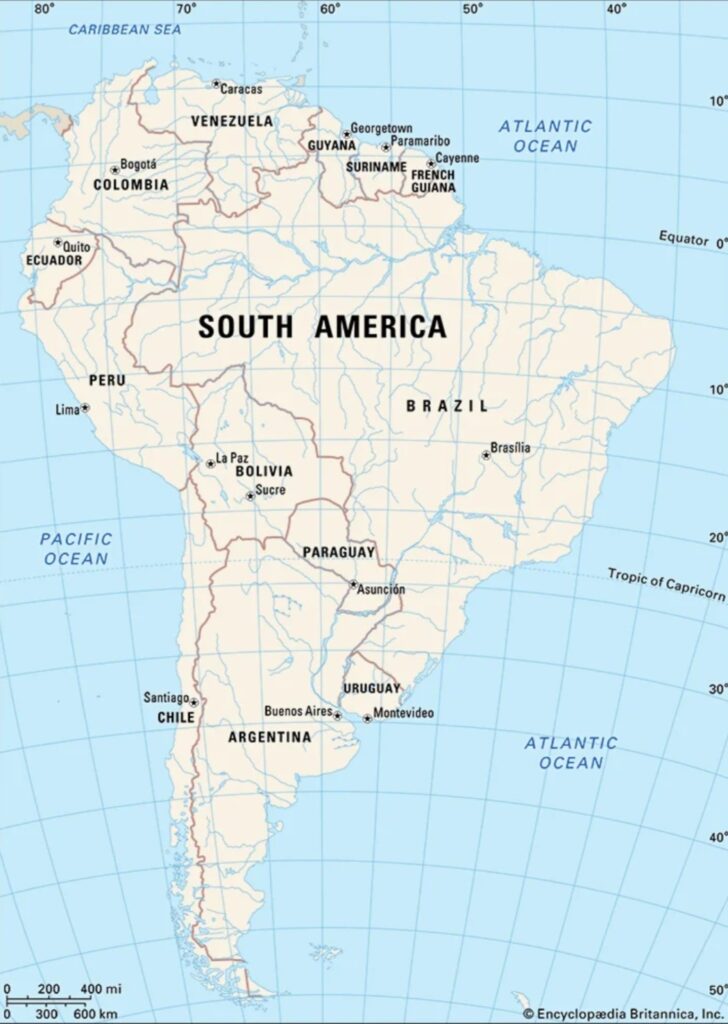

The countries of South America are the likes of Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, Venezuela and French Guiana (which is an overseas territory of France, not a sovereign state per se). The population of South America, is officially estimated to be between 438–453 million during 2025, as per United Nations (UN) Data.

As Alberto Methol Ferré has famously proposed “a continentalist outlook of South America as a geopolitical unit, within a Latin American national dimension”, it indicates the desired cohesion, integration and shared identity.

Historical Underpinnings

It certainly is strange and fascinating in equal measure, that most countries of South America (except Suriname), despite exercising sovereignty and achieving independence since the 19th century still get overlooked. A continent so rich in natural resources, so crucial to the global oil supply chains and still struggling to break free from the shackles of rampant corruption, rising crime rates, declining economies, environmental degradation and a serious drug problem? The questions are varied and their reasons are significantly embedded in the whirlwind of geopolitical undercurrents.

To reconstruct the past, it is imperative to revisit and recall it first. South America’s colonial past, especially the Spanish-Portuguese legacy reverberates centuries later in its economic traditions and popular culture, spheres that manifest into geopolitical ramifications. The history of economic dependency through an extractive model, later followed by becoming a reluctant battleground in the struggle for ideological supremacy between the US and the erstwhile Soviet Union in the second half of 20th century have been markers of the journey that the region has had.

While the Spanish and Portuguese empires turned South America into an exporter of raw commodities — silver from Potosí (Bolivia), gold from Brazil, sugar and coffee from plantations — this hampered the region’s self sufficiency, autonomy and agency. With that kind of a historical backdrop, the continent’s economy continues to be entrenched with inequality and dependency on external markets. This pattern explains why South America has always been a supplier of strategic resources (then silver, gold, sugar; now oil, lithium, soy).

The Cold War showed that control of South America mattered for ideological balance and global security. Today’s great power rivalry (U.S. and China, with Russia re-emerging) is a direct echo of these tensions. Many South American states although resisted full alignment with either superpower. Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) had strong Latin American participation (e.g., Argentina, Peru, Brazil to some extent). Countries pursued regional initiatives to reduce dependence (like early precursors to Mercosur “Mercado Común del Sur”.

These non-aligned tendencies established a tradition of strategic autonomy, which continues till date.

Political Ethos & Chaos

The political fiber of the continent, despite varying country-wise, also has a thread that has held them all together, that thread being of chaos and instability. With the onset of the Pink Tide 1.0 in the 2000s, left-leaning leaders gaining ground (like Chávez, Lula, Morales) and the subsequent right-wing resurgence in the 2010s, which has now gone back to left (Lula’s comeback, Boric in Chile, Petro in Colombia) shows the diversity of public opinion, overpowering the waves of real politik that the world has tried time and again to associate South America with.

This frequent democratic fragility, almost across the board, including the coups like that of Bolivia in 2019, impeachment crises (like those in Brazil, Peru), have had repercussions on the policy swings that have hindered long-term strategies to either unite, or integrate into the changing tech-savvy world order.

Colombia’s cocaine trade menace, organized crime spilling into politics, the Venezuelan crisis forcing millions of refugees to look for shelter and opportunities elsewhere, bankruptcy, hyper-inflation has destabilized the path to mainstreaming of modernity, innovation and collaboration.

Whether it’s Argentina’s Falkland Islands unresolved issue with the United Kingdom (UK), or the Venezuela-Guyana territorial conflict regarding the Essequibo region, the equations are subject to change and scrutiny within South America as well as outside, making it a geopolitically charged entity.

Natural resources-Exploited yet under-utilized

The continent has a lot to offer – like soybeans, lithium, copper, and oil. Venezuela holds the world’s largest oil reserves, but on the flip side, the recent instance of aggressive posturing by the U.S. near its coast (some have gone on to the extent of terming it as an instance of doorstep warfare) and the not so friendly rapport that President Lula from Brazil or President Nicolas Maduro from Venezuela share with President Trump cast aspersions on the viability and feasibility of maximizing the potential of these resources.

Brazil and Argentina are now big players in exporting soybeans, especially because of the trade issues between the US and China, which has made China look for more soybean suppliers in Latin America. This makes South America a stakeholder in the global food supply chain. Also, Argentina’s new policies under President Javier Milei and other countries in the region making it easier for businesses have boosted investors’ hope and confidence. Plus, the continent is key for clean energy, with Chile, Bolivia and Argentina (the Lithium Triangle with 60% of global reserves) providing lithium used in batteries, putting South America on the map in green technology. Regarding renewable energy potential, the wind energy landscape in Patagonia and the hydropower caliber of Brazil are treasure troves of geo-economic transformation waiting to be unlocked and unleashed.

Expanding relationship with China and its alarming aspects

China has solidified its position as South America’s leading trading partner by heavily investing in energy, infrastructure of railways and ports, and military sectors through the Belt and Road Initiative, of which various South American countries are signatories. In 2025, China hosted regional leaders and announced a US$ 9 billion investment credit line, reinforcing its economic influence. Chinese companies have filled the gap left by declining Western investment, building goodwill through aid, investment, and cultural diplomacy. Beijing’s increasing military cooperation, particularly with Venezuela, has raised concerns in Washington regarding the strategic implications for hemispheric security. Another area of suspicion is the Chinese technological and military footprint (courtesy Huawei’s operations under the scanner, satellite stations in Argentina etc).

The shifting alliances on the Taiwan issue—most recently highlighted by Honduras switching recognition to China in 2023—illustrates Beijing’s growing diplomatic influence. More importantly, Beijing’s history of charging exorbitantly high rates of interest when lending and wolf warrior diplomacy coupled with expansionist tendencies repeatedly put on display, the risk of debt dependency is as real as one can safely speculate.

Strategic partnership with India

Meanwhile, the diplomatic engagement with India and the geopolitical vitality that it has in New Delhi’s outlook has been on an upward trajectory. South America, collectively, now has the defining choice to make – to continue to work with India as a strategic partner in mobilizing the Global South and be the voice of reason in multilateral forums.

The transition from non-alignment to all-alignment, as long as there is issue-based cooperation and the strategic autonomy stays intact, has been India’s policy so far in these unprecedented times of sanctions. With South America on-board, and the diversity, credibility and newness that it brings, the sky is the limit to realize mutually beneficial outcomes. Therefore, South America clearly has a role to play bridging the divide and communication gap that exists and persists in the world, in the form of camps and alliances.

Security and regional equations

An economic bloc like the Mercosur, but with issues of uneven integration has had some history. UNASUR (Union of South American Nations) meanwhile stands rather weakened and UN CELAC (the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States) signals a revitalizing attempt at ensuring Latin American unity. With the newfound activity within BRICS (Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa), of which Brazil is a permanent member and from which Argentina withdrew is another instance of different countries making different choices, often at the expense of contrast. While this does signify autonomy, but as a whole, it is also how fragmented the region really is.

South America’s ambitions to influence global standards on development, climate change, and conflict resolution are highlighted by Brazil’s 2025 BRICS chairmanship and the region’s heightened participation in international fora like the G20 (Group of 20).

Its role as a resource-rich periphery still defines its geopolitical importance, after being historically turned it into a strategic arena where resources, ideology, and autonomy collide. These same factors corroborate why the region is even more geopolitically vital today.

Geographical and environmental domain-Climate politics

The geo-strategic location of South America, if we were to look at it from the lens of Rimland theory or Mackinder’s theory, is a myriad of gateways to oceanic spaces and land borders. The presence of the “lungs of the Earth” Amazon rainforest in the context of biodiversity preservation and conservation and also transnational security, the proximity to the Panama Canal with respect to movement in world trade, the direct access to both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans as trade routes, the Andes mountains as resource hub and the Atacama desert as a natural barrier – are all to be factored in while ascertaining the sheer impact it has on the global ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) goals.

The politics surrounding climate change has also assumed a more pronounced geopolitical character with deforestation, illegal unchecked mining, wildfires and overall climate negotiations taking the centre stage in what we now know as climate justice amidst fulfillment of common but differentiated responsibilities. This very climate security ties South America to global future.

The US conundrum

With the Monroe Doctrine (1823) declaring Latin America as the US “backyard”, thereby shutting out European colonial ambitions, South America has always been fundamental to U.S. hemispheric stability and security doctrine. Throughout the 20th century, Washington is often found to be somewhat considered by many, as party to interventions, coups, and economic pressure to secure its dominance. The classic case of Chile (1973) when the U.S. supported Pinochet against socialist Salvador Allende serves as a famous example.

One famous school of thought amongst geopolitical commentators suggests that this is partly because of their geographical proximity to a superpower that at times overshadowed/overpowered them, unintentionally and otherwise. Albeit the U.S. influence off late has been viewed as declining with rise of China, Russia, and regional assertions, but it still holds well in the spheres of military, migration, anti-narcotics operations. Today, the U.S. faces the historical baggage and legacy of these policies and rightly so, as many South Americans remain persistently uncomfortable with, or skeptical of American influence and power.

Economic sustainability

South America has historically been the supplier of raw materials in global supply chains. However, as the circumstances and economic priorities have changed over the years, the situation is a lot more optimistic brimming with recovery and expected reforms, of which increased geopolitical relevance is a natural consequence.

Brazil, apart from being a full-time G-20 member, is the continent’s largest economy, followed by Argentina and Colombia. While South America’s total nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2025 is projected at around US $4.3 trillion. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (UN ECLAC) estimate a real GDP growth rate for South America of 2.7% in 2025, driven by recoveries in Argentina and Ecuador and steady expansion in Brazil, Colombia, and Paraguay.

As South America has largely and consciously chosen to stay neutral as tensions rise between the United States, China, and the European Union. This nuanced approach enables South America to position itself as an important hub for foreign direct as well as institutional investments. For example, the recent completion of trade talks between the EU and Mercosur (bloc with Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay) in December 2024 shows how South America is working to build partnerships with different groups. Over 64% of local business leaders see the current split in global trade as a chance to grow.

Way forward

South America’s geopolitical importance ought to be rooted in realism, with special emphasis on its strategic location, resource-richness and climate change-related food security to be utilized as a leverage while carrying out its balancing act between various world powers.

As South America is no longer a passive participant or a dormant observer, but a key arena in the 21st-century multi-polar order, but it still faces multiplicity of challenges like political instability, economic inequality, corruption, water shortage, weak logistical base, and regional ideological fragmentation. By cracking new trade agreements and treaties, welcoming foreign investment, and carefully handling relationships with major world powers, the continent as a whole is coming up as a key player.