By: Khushbu Ahlawat, Consulting Editor, GSDN

European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and India: Strategic Economic Partnership

The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) is an intergovernmental organisation established by the Stockholm Convention in 1960 with the purpose of promoting free trade and economic integration among its member states. EFTA originally included seven countries but now consists of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland. This bloc operates as a trade partnership distinct from the European Union (EU), facilitating liberalised trade policies, removing tariffs, and fostering closer economic cooperation with global partners through free trade agreements (FTAs).

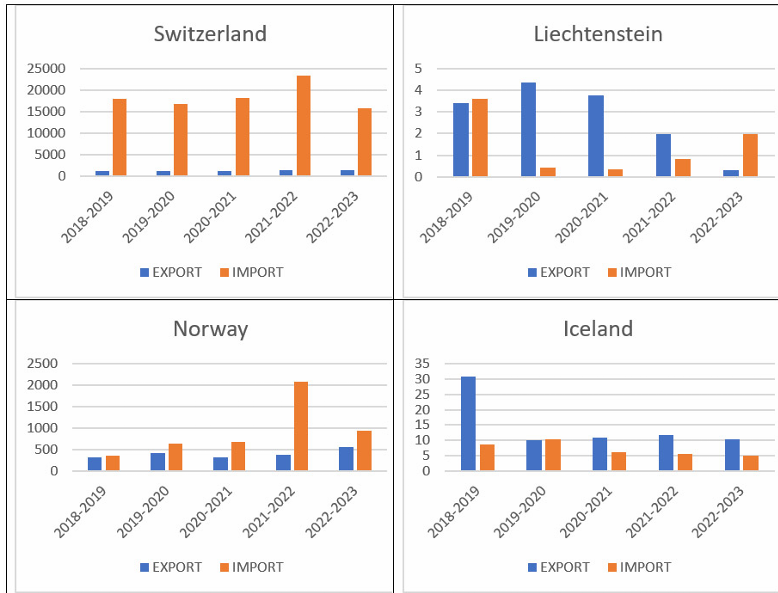

India’s engagement with EFTA has culminated in a major milestone: the Trade and Economic Partnership Agreement (TEPA) between India and the four EFTA countries was signed on 10 March 2024 after long negotiations and subsequently entered into force on 1 October 2025. This marks India’s first comprehensive trade pact with four developed European economies outside the EU framework. In the fiscal year 2022-23, EFTA ranked as India’s fifth-largest trading partner, trailing the EU, the United States, the UK, and China, with two-way trade valued at USD 18.65 billion and India recording a trade deficit of USD 14.8 billion; Switzerland stands out as India’s largest partner within the bloc, followed by Norway. Exports to EFTA dominated in machinery and pharmaceuticals, while Indian exports were led by organic chemicals.

The TEPA is designed not only to reduce tariffs on goods such as pharmaceuticals, machinery, watches, and processed foods but also to liberalise trade in services, expand investment flows and deepen economic cooperation. Over a 15-year period, the EFTA members have pledged about USD 100 billion in investments into India, with an aim to generate one million direct jobs, making it one of the most ambitious investment commitments in any Indian trade deal to date. By creating easier market access, streamlined customs procedures, and mutual recognition in professional and services domains, this partnership supports India’s broader goals of enhancing global supply chain integration and strengthening industrial competitiveness.

The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) was established in 1960 under the Stockholm Convention, with the objective of promoting free trade and economic cooperation among its member states. India–EFTA relations have steadily deepened over the decades, culminating in a major breakthrough on 10 March 2024, when India and the four EFTA countries signed the Trade and Economic Partnership Agreement (TEPA) in New Delhi, marking India’s first comprehensive trade pact with this European bloc. This growing engagement is reflected in trade figures as well—during FY 2022–23, bilateral trade between India and EFTA stood at USD 18.65 billion, underscoring the expanding economic interdependence and strategic relevance of the partnership.

In recent news, the TEPA implementation has been widely highlighted for its potential to boost bilateral trade, attract large-scale investments, and generate employment, with officials from both sides marking the agreement as pivotal in enhancing economic relations between India and European economies outside the EU framework.

TEPA as a Strategic Reset in India–EFTA Economic Relations

The India–EFTA Trade and Economic Partnership Agreement (TEPA) represents a strategic reset after a decade-long pause in negotiations, which had stalled in 2013 due to differences over market access and investment commitments. Changing global geopolitics—particularly supply-chain disruptions, heightened trade uncertainty, and a shared interest in reducing over-dependence on China—created fresh momentum for the deal. Finalised in March 2024, TEPA consists of 14 comprehensive chapters covering market access for goods, rules of origin, trade facilitation, services, investment promotion, intellectual property rights (IPRs), and sustainable development, making it one of India’s most wide-ranging trade agreements with developed economies.

A standout feature of TEPA is its investment-centric architecture. EFTA has committed to facilitating USD 100 billion in foreign direct investment into India over a 15-year period, explicitly linked to direct job creation, while excluding volatile portfolio flows. This makes TEPA unique among India’s trade agreements, as it legally ties investment to employment outcomes. The agreement also reinforces strong IPR protections, aligned with the WTO’s TRIPS framework, addressing long-standing concerns of EFTA members—particularly Switzerland—while maintaining India’s regulatory flexibility in public interest areas such as healthcare and access to medicines.

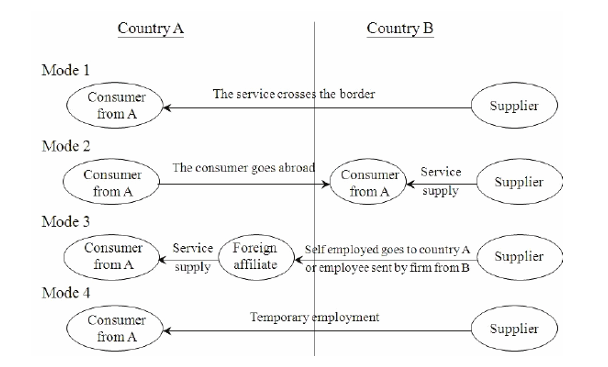

On market access, TEPA demonstrates a calibrated balance. EFTA has offered tariff concessions on 92.2% of tariff lines, covering 99.6% of India’s exports, including full access for 100% of non-agricultural products and concessions on Processed Agricultural Products (PAPs). India, in return, has liberalised 82.7% of its tariff lines, covering 95.3% of EFTA exports, while safeguarding sensitive sectors such as dairy, soy, coal, and select agricultural goods. The agreement also advances services liberalisation, with enhanced access across Mode 1 (digital delivery), Mode 3 (commercial presence), and Mode 4 (movement of professionals), alongside provisions for Mutual Recognition Agreements in professions like nursing, architecture, and chartered accountancy. Recent policy discussions have highlighted TEPA’s role as a gateway for Indian firms into wider European markets, with Switzerland emerging as a strategic base due to its strong services linkages with the EU—positioning TEPA as both a trade pact and a long-term geo-economic partnership.

Why the India–EFTA TEPA Is a Strategic and Economic Game-Changer?

The India–EFTA Trade and Economic Partnership Agreement (TEPA) is significant primarily because of its investment-driven design, with EFTA countries committing to USD 100 billion in Foreign Direct Investment over 15 years, directly linked to job creation. This scale of assured FDI is unprecedented in India’s trade agreements and is expected to accelerate development in infrastructure, advanced manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, clean energy, and high-end technology sectors. Beyond capital inflows, TEPA promotes technology transfer, R&D collaboration, and vocational skill development, which aligns closely with India’s long-term growth needs and its demographic dividend. Recent official statements following the agreement’s operationalisation have highlighted TEPA as a “model trade pact” that combines market access with tangible developmental outcomes rather than purely tariff reductions.

From a domestic policy perspective, TEPA strongly reinforces flagship initiatives such as “Make in India” and “Atmanirbhar Bharat.” By incentivising local manufacturing and encouraging EFTA firms to establish production bases in India, the agreement supports import substitution while embedding India deeper into global value chains. Simultaneously, TEPA is expected to boost India’s services exports, particularly in IT, business services, professional services, and digital delivery, aided by commitments on Mode 1, Mode 3, and Mode 4 access. Indian consumers also stand to gain through greater access to high-quality Swiss and Nordic products—such as watches, chocolates, processed foods, and precision instruments—at more competitive prices as customs duties are gradually phased out over a decade. Recent trade commentary has emphasised that this balance between consumer welfare and domestic industry protection makes TEPA politically and economically sustainable.

At a broader strategic level, the India–EFTA deal carries geopolitical and systemic significance. It strengthens India’s economic footprint in Europe outside the EU framework, diversifies trade partnerships, and reduces dependence on a narrow set of trading partners amid global uncertainty. TEPA also sets a precedent for future trade negotiations with the UK and the European Union, offering a blueprint for integrating market access, investment commitments, intellectual property protection, sustainability, and government procurement into a single framework. With its emphasis on TRIPS-aligned IPR standards, environmental stewardship, and rules-based trade, recent policy analyses describe TEPA as positioning India not just as a market, but as a credible rule-shaper and champion of free trade and economic cooperation in the evolving global trade order.

India’s Bilateral Engagements with EFTA Nations: Strategic Depth Beyond Trade

India’s relations with individual EFTA member states predate the TEPA framework and reflect long-standing diplomatic, economic, and strategic convergence. India–Norway ties, established in 1947, have evolved from traditional diplomacy into forward-looking cooperation in sustainability, maritime governance, and polar research. The launch of the India–Norway Task Force on Blue Economy in 2020 marked a significant shift toward ocean-based sustainable development, renewable energy, and fisheries management. Scientific collaboration remains a cornerstone, highlighted by HIMADRI, India’s Arctic research station in Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard, which has gained renewed relevance amid global climate governance debates and Arctic geopolitics. In the context of TEPA, Norway’s support for India’s inclusion in key export control regimes and its emphasis on green growth align closely with India’s strategic and environmental priorities.

India–Switzerland relations form the economic backbone of India’s engagement with EFTA. Since the Treaty of Friendship in 1948, Switzerland has emerged as India’s largest trading partner within EFTA and a critical source of high-value investment, technology, and precision manufacturing expertise. The presence of over 300 Swiss companies in India, alongside major Indian IT firms operating in Switzerland, reflects a mature and mutually embedded economic relationship. Recent developments surrounding the India–EFTA TEPA (signed in 2024) have further elevated Switzerland’s role as a gateway for Indian firms into wider European markets, particularly in services, pharmaceuticals, innovation, and R&D. Ongoing dialogues on intellectual property protection, skill mobility, and investment-linked job creation underscore both opportunity and friction, making Switzerland central to the agreement’s success.

India’s engagement with Iceland and Liechtenstein, though smaller in scale, carries disproportionate strategic value. India–Iceland relations, established in 1972, have intensified since the mid-2000s, with Iceland becoming the first Nordic country to support India’s permanent UNSC membership—a politically significant gesture. Recent MoUs on renewable energy, geothermal technology, green hydrogen, and decarbonisation reflect convergence on climate action and clean energy transitions, areas where Iceland holds niche expertise. Meanwhile, India–Liechtenstein ties, formalised in 1993, are largely investment-driven, with FDI inflows—though modest—reflecting Liechtenstein’s role as a financial and investment hub. Under TEPA, these smaller EFTA economies gain strategic relevance as innovation partners and niche investors, reinforcing India’s broader objective of diversified, high-quality economic engagement with Europe beyond the EU framework.

Critical Challenges and Structural Constraints of the India–EFTA Trade Agreement

Despite its potential benefits, the India-EFTA trade agreement faces several key challenges that warrant attention. Firstly, India’s selective exclusion of sectors like agriculture and dairy from significant tariff reductions may limit the advantages for EFTA exporters, particularly regarding India’s substantial imports of gold, mainly from Switzerland. Moreover, the agreement includes a provision allowing India to adjust duty concessions if the committed investments of USD 100 million fail to materialize, introducing a layer of accountability. Concerns also arise regarding data exclusivity provisions proposed by EFTA nations, which could hinder access to critical clinical trial data for generic drug manufacturers. Addressing the vast income disparities between India and EFTA countries is essential for ensuring equitable opportunities and fostering mutual growth. Additionally, streamlining non-tariff barriers such as differing product standards and technical regulations is crucial to prevent hurdles for exporters and ensure compliance with market requirements. Lastly, domestic opposition from Indian sectors facing EFTA competition underscores the importance of engaging stakeholders to address potential job losses and concerns about unfair competition.

Conclusion

The India–EFTA Trade and Economic Partnership Agreement represents far more than a conventional free trade arrangement; it is a strategic experiment in aligning trade liberalisation with investment-led development, employment generation, and technological advancement. By combining deep market access with a legally anchored USD 100 billion investment commitment, TEPA signals a shift in India’s trade diplomacy—from tariff-centric negotiations to outcome-oriented economic partnerships. It strengthens India’s integration into high-value European supply chains, enhances services exports, and positions the country as a credible destination for long-term, quality capital in a period of global economic fragmentation.

However, the agreement’s long-term success will hinge on effective implementation and careful management of structural asymmetries. Persistent concerns over data exclusivity, non-tariff barriers, income disparities, and domestic sectoral resistance highlight the need for continuous stakeholder engagement, regulatory coordination, and policy flexibility. India’s ability to safeguard public interest—particularly in healthcare and agriculture—while remaining an attractive investment destination will be central to sustaining political and economic consensus around TEPA.

Ultimately, TEPA serves as a benchmark for India’s future engagements with advanced economies, including ongoing negotiations with the UK and the EU. If implemented with institutional coherence and strategic foresight, the agreement could redefine India’s role from a rule-taker to a rule-shaper in the global trade order, reinforcing its image as a champion of free trade, sustainable development, and equitable economic cooperation. In this sense, the India–EFTA partnership is not merely about trade expansion—it is a test case for India’s evolving global economic strategy in the 21st century.

About the Author

Khushbu Ahlawat is a Research Analyst with a strong academic background in International Relations and Political Science. She has undertaken research projects at Jawaharlal Nehru University, contributing to analytical work on International and Regional security issues. Alongside her research experience, she has professional exposure to Human Resources, with involvement in Talent Acquisition and organizational operations. She holds a Master’s degree in International Relations from Christ University, Bangalore, and a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science from the University of Delhi.