Global Strategic and Defence News (GSDN) started its foray on November 11, 2022 as a forum to provide accurate analysis on geopolitical and defence issues that concern the world at large

“Gaza A ‘Killing Field’, Warns UN Chief As Humanitarian Crisis Deepens; Indonesia Offers Refuge To 1,000 Displaced

UN Secretary-General António Guterres has described Gaza as a “killing field” where civilians are trapped in an “endless death loop,” as humanitarian conditions worsen under Israel’s continued blockade and renewed military offensive.

“Aid has dried up, and the floodgates of horror have re-opened,” Guterres said on Tuesday, urging immediate global intervention. His remarks came shortly after six UN agencies issued a joint plea to world leaders to act swiftly to ensure the flow of food and essential supplies into Gaza.

Since Israel imposed a full blockade on March 2, following the collapse of a temporary ceasefire, the situation has deteriorated rapidly. Hamas had refused to extend the truce, accusing Israel of failing to uphold its commitments. On March 18, Israel resumed airstrikes and ground operations, which the Hamas-run health ministry says have killed 1,449 Palestinians since then. The Israeli military maintains that it targets Hamas fighters, not civilians.

Guterres reminded the international community that Israel, as the occupying power, is obligated under international law to allow the entry of humanitarian aid. “The current path is a dead end—totally intolerable in the eyes of international law and history,” he said.

Israel has rejected the UN’s characterisation. Foreign Ministry spokesperson Oren Marmorstein accused Guterres of “spreading slander against Israel,” stating that over 25,000 aid trucks had entered Gaza during the 42-day ceasefire period. “There is no shortage of humanitarian aid in the Gaza Strip,” he claimed.

However, the reality on the ground tells a different story. UN agencies report that Gaza’s bakeries supported by aid groups have shut down, markets lack fresh produce, and hospitals are rationing painkillers and antibiotics.

The agencies warned that Gaza’s health system is barely functioning and that supplies are critically low. “With the tightened Israeli blockade now in its second month, we appeal to world leaders to act—firmly, urgently and decisively,” the statement read.

Their call concludes: “Protect civilians. Facilitate aid. Release hostages. Renew a ceasefire.”

Aid Halted, Ceasefire Broken, Death Toll Rises

The two-month ceasefire saw an increase in humanitarian aid and a high-profile prisoner exchange: Hamas released 33 hostages (eight of them dead) in exchange for approximately 1,900 Palestinian prisoners held by Israel. However, since fighting resumed, Gaza’s health ministry, run by Hamas, reports over 50,810 Palestinian deaths, including at least 58 people killed in the last 24 hours alone.

Israeli airstrikes overnight reportedly killed 19 people, including five children, when a home in Deir al-Balah was struck. Additional casualties were reported in Beit Lahia and areas near Gaza City.

Meanwhile, journalists have also come under fire. The Palestinian Journalists Syndicate confirmed that Ahmed Mansour, a journalist injured during an Israeli strike on a media tent in Khan Younis, succumbed to his injuries. The strike also killed fellow journalist Helmi al-Faqaawi. The Israeli military claims the intended target was another journalist, Hassan Eslaih, whom it accuses of being affiliated with Hamas.

Indonesia Steps Forward to Shelter Refugees

Amid the unfolding crisis, Indonesia has offered to temporarily house 1,000 refugees from Gaza, marking one of the first large-scale offers of refuge for Palestinians displaced by the war. President Prabowo Subianto announced the plan as he began a diplomatic trip to the Middle East, including visits to Turkey, Egypt, and Qatar.

“We are ready to evacuate the wounded, the traumatized, and the orphans,” Prabowo said, emphasizing that the evacuees would stay in Indonesia only until they recover and it is safe to return to Gaza.

The move aligns with Indonesia’s long-standing support for the Palestinian cause. While Jakarta has rejected past proposals to permanently relocate Palestinians out of Gaza, it now appears willing to accommodate those affected, at least temporarily, indicating a shift in Indonesia’s humanitarian outreach.

Diplomatic Overtures and a Fraying Peace

Though Indonesia and Israel have no formal diplomatic ties, reports last month indicated a special communication channel had been established to explore a pilot work program for Gazans in Indonesia. That plan remains unrealized, but Indonesia’s latest offer may signal a broader willingness to engage constructively with the international community amid the spiraling conflict.

Indonesia, under President Prabowo Subianto’s leadership, continues to assert itself as a rare Muslim-majority voice not only for peace but for practical humanitarian intervention. Even before officially assuming office, Prabowo expressed willingness to send peacekeeping forces to Gaza if needed, an offer that set him apart from many world leaders who have stuck to diplomatic condemnation.

Now, with his recent commitment to temporarily house 1,000 Palestinians, Prabowo is positioning Jakarta as an active participant in shaping Gaza’s humanitarian recovery, not just a bystander.

Trump’s ‘Riviera’ Vision and the Relocation Controversy

In contrast, U.S. President Donald Trump sparked a firestorm of criticism in February with his suggestion that the U.S. “take over” Gaza and turn it into a “Middle East Riviera.” Trump’s initial comments proposed the relocation of Gazans to Egypt, Jordan, or other countries, a plan widely seen as both politically inflammatory and morally indefensible.

Although Trump has since backtracked, saying no Gazans would be forcibly expelled, his comments exposed a deeper debate brewing within certain global and regional corridors of power: whether Gaza’s population should stay or be encouraged to leave.

Far-Right Factions and Secret Deals

Some far-right elements within Israel’s governing coalition openly support using the war to reestablish settlements in Gaza and consider depopulation of the Strip a strategic goal. The Israeli government, while not officially endorsing mass displacement, has reportedly been involved in covert discussions with African nations such as Congo to facilitate emigration of thousands of Gazans. These secret contacts, first revealed by Zman Israel, have sparked alarm and criticism, even within parts of the international community aligned with Israel.

Arab Nations Push Back—But With Nuance

Publicly, Arab nations have firmly rejected any efforts to forcibly displace Palestinians. Egypt, in particular, has repeatedly affirmed its “absolute and final rejection” of such proposals. When a Lebanese report in March claimed that President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi was open to temporarily housing half a million Gazans in northern Sinai, Cairo denied it outright.

Instead, key Arab organizations have backed a counterproposal, advocating for Palestinians to remain in Gaza while an independent technocratic committee governs the territory for six months, after which control would be transferred to the Palestinian Authority. This alternative plan puts the emphasis squarely on rehabilitation without population displacement.

Where Does the U.S. Stand?

The U.S. has appeared non-committal. While Trump’s initial statements alarmed many, current efforts led by Mideast envoy Steve Witkoff are more focused on brokering a new ceasefire and a hostage-release deal. According to reports by Axios, there is no active push from the U.S. administration to advance the Gaza relocation plan. However, the ambiguity has only fueled speculation and distrust in Arab and international circles.

Human Cost of War Continues to Climb

Since the war began on October 7, 2023, after a Hamas-led attack on southern Israel that killed 1,200 people and saw 251 kidnapped, more than 50,000 people have died in Gaza according to the enclave’s Hamas-run health authorities. Over 115,000 have been wounded, with entire neighborhoods reduced to rubble. The staggering toll, while difficult to independently verify, has only increased the urgency for a comprehensive and just rehabilitation plan.

The Last Bit

As regional and global powers jockey for influence over Gaza’s post-war future, Indonesia’s voice stands out, not just for its moral clarity but also for its willingness to act. While relocation proposals and forced migration remain controversial and largely rejected, the window for genuine reconstruction, centered on Palestinian rights and participation – is rapidly narrowing.

The question that remains is whether the world will follow Jakarta’s lead, or continue down a path of geopolitical calculations that leave Gaza’s people as pawns in a game they never asked to play.

Beijing’s Next-Gen Warbirds Exposed, J-36, J-50 Sightings Stir U.S. F-47 Urgency. Why Does China’s Secret Next-Gen Stealth Plane Have Three Engines?

A dramatic new video showing China’s futuristic, tailless, triple-engine fighter jet, likely the J-36, flying low over a busy highway has reignited global discussion about the intensifying sixth-generation arms race between the U.S. and China. The aircraft was spotted near the Chengdu Aircraft Industry Group’s facility in Sichuan, where it is believed to have been developed.

Inside the J-36. Trijet, Stealth, and a Bold New Design

Military analysts have dubbed the aircraft the J-36, a sixth-generation stealth jet featuring a flying wing design with no vertical stabilizers. The standout feature is its rare trijet configuration – two intakes under the wings and a third mounted dorsally behind the cockpit – breaking away from the more conventional twin-engine setups seen in most modern fighters.

According to defense expert David Cenciotti, the aircraft’s configuration suggests enhanced thrust and redundancy, and its belly appears to house internal weapons bays for long-range missiles. Other key design elements include a streamlined canopy, diverterless supersonic inlets (DSI), and split ruddervators, an unusual aerodynamic feature that implies a focus on stealth, range, and speed.

The latest footage reveals a closer-than-ever view of the aircraft in flight, showcasing its heavy-duty landing gear and what some believe is a side-by-side seating configuration, contrary to earlier assumptions of tandem seating.

Across the Pacific, U.S. Pushes Forward with F-47 and NGAD

While China’s J-36 dominates aviation chatter, the U.S. has not been idle. Last month, President Donald Trump announced that Boeing had secured the contract to build America’s sixth-generation fighter, dubbed the F-47, under the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program. According to Trump, the prototype has been flying for about five years, though the Pentagon has yet to confirm specifics due to the program’s classified nature.

Multiple prototypes from defense giants Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman are believed to have flown already, but the timeline for deployment remains unclear. The F-47 contract, awarded on March 21, only covers the engineering and development phase along with a few test aircraft for evaluation.

China’s Broader Sixth-Gen Ambitions – J-36 and J-50 Emerge

China’s ambitions go beyond just one aircraft. On the same day the J-36 first surfaced in December, images also appeared of another stealthy, tailless jet, believed to be the J-50, developed by the Shenyang Aircraft Corporation. Unlike the J-36’s trijet build, the J-50 is a twin-engine aircraft with a sleeker, more compact frame and appears to use a lambda wing design.

The PLA has not officially acknowledged either aircraft, but China’s state-run Global Times ran a story citing experts who said the sightings suggest significant progress in sixth-generation aviation technology.

April 8 Sighting of J-50 Offers New Clues

The clearest footage yet of the J-50 emerged on April 8, showing the aircraft in flight, its third public appearance. Observers noted several distinctive features – twin engines, 2D thrust vectoring nozzles, tricycle landing gear with a dual nose wheel, diverterless inlets, and possibly an electro-optical sensor bulge beneath the cockpit.

Despite its smaller size compared to the J-36, the J-50’s stealthy shaping, large nose (possibly housing next-gen avionics), and movable wingtips suggest it’s designed for networked, air-dominance missions in contested environments. The design strongly echoes the PLAAF’s J-20 in terms of stealth characteristics.

Visibility by Design?

The emergence of multiple high-quality images and videos, particularly of the J-36 flying low over public roads, has led some observers to speculate that China wants the world to see its progress. While military programs in China have traditionally been shrouded in secrecy, the power of social media, especially as these jets fly over populated areas, has made it nearly impossible to keep things under wraps.

Some compare this to the U.S. advantage of having remote and restricted areas like Area 51 for testing, whereas China’s prototypes often take off from more visible locations.

Who’s Winning the Sixth-Gen Race, Neck-and-Neck or Not Quite?

While the U.S. claims to be ahead, China’s public testing of two separate sixth-gen prototypes, J-36 and J-50, suggests it is rapidly catching up. Some analysts believe Trump’s recent push to accelerate the F-47 program may have been spurred by China’s recent reveals.

That said, the F-47 and NGAD programs remain deeply classified, and the true extent of American progress may not be fully visible. Meanwhile, China’s accelerated public testing of its prototypes creates the impression that it might be in the lead.

Why Does China’s Secret Next-Gen Stealth Plane Have Three Engines? The Answer May Lie in Power Needs, Not Just Thrust

When it comes to stealth fighters, the global design philosophy has been fairly consistent – one or two engines are considered sufficient. That’s why the emergence of China’s newly spotted sixth-generation stealth aircraft, reportedly called the J-36, with a striking three-engine configuration, has stirred considerable curiosity among defense analysts and aviation watchers alike.

The aircraft was seen on December 27 flying over the Chengdu Aircraft Corporation’s airfield (the same firm that produces the fifth-generation J-20 stealth fighter) with a sleek, tailless triangular design optimized for radar evasion, the J-36 bears all the hallmarks of cutting-edge stealth tech. Yet, it’s those three engine nozzles that defy conventional logic.

Why three? There are two prevailing schools of thought.

One view attributes the design to China’s ongoing engine development struggles. While countries like the U.S. rely on incredibly powerful single engines, such as the Pratt & Whitney F135, which delivers 20 tons of thrust for the F-35 – China’s WS-10 engines still trail behind, producing around 15 tons at full throttle. To match the performance of Western fighters, engineers may simply have added a third engine to compensate for lower individual output. If true, this would be less a bold innovation and more a workaround rooted in technological gaps.

But there’s another, more compelling possibility: this design may be purpose-built for power, not just propulsion. Modern combat aircraft increasingly serve as flying sensor hubs, command posts, and potentially even energy weapons platforms. As the Chinese military pushes toward manned-unmanned teaming (where a human pilot orchestrates a swarm of loyal wingman drones) airborne data management, communications, and AI systems demand serious onboard power. Add in the possibility of future integration of directed energy weapons like high-energy lasers or microwave-based systems, and the need for robust power generation becomes clear.

Two engines might offer the thrust needed to fly, but three could ensure the J-36 has the electrical muscle for battlefield dominance.

China’s Sixth-Generation Warfare Doctrine

The J-36 may be a critical chess piece in China’s overarching sixth-generation military doctrine. Beijing’s defense strategy is increasingly shaped by two priorities: developing asymmetric capabilities to counter U.S. superiority, and leapfrogging legacy systems to seize technological leadership in future conflicts.

Unlike earlier eras where China was content with incremental advancements, the sixth-gen race is being approached with a sense of urgency. Manned-unmanned teaming, AI integration, stealth-first designs, and energy-based weaponry are no longer theoretical—they’re rapidly becoming operational imperatives. In this context, the J-36 appears as a platform built not just for air dominance, but for digital and electromagnetic dominance as well.

Its three engines may support more than just energy-intensive weapons or drone coordination. They could power sophisticated jamming suites, advanced sensor fusion, or even satellite uplinks to support long-range command-and-control functions. China is aiming not just for a fighter jet, it’s aiming for a flying battlefield brain.

And with tensions escalating in the Taiwan Strait and the Indo-Pacific turning into a strategic tinderbox, time may be pushing China to test bold, unconventional configurations like the J-36 to gain a decisive edge before the next global paradigm shift.

J-36 vs. The West: NGAD, FCAS, and the Diverging Paths of Sixth-Gen Evolution

If China’s J-36 is the dragon’s wing, the U.S. and its allies are forging their own predators in the sky – each unique in approach, but unified by similar end goals: survivability, connectivity, and lethality in the most contested environments.

United States – NGAD (Next Generation Air Dominance)

The U.S. Air Force’s NGAD program remains highly classified, but confirmed reports suggest the demonstrator has already flown. Key takeaways include a tailless stealth design, hyper-connectivity, and a focus on teaming with autonomous drones known as Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCAs). NGAD is likely powered by a single or twin advanced adaptive engine, offering variable cycle capabilities to balance thrust, speed, and fuel economy. Notably, the U.S. continues to lean on its unrivaled engine tech to avoid multi-engine complexity.

Europe: FCAS (Future Combat Air System)

Led by France, Germany, and Spain, FCAS aims to field a sixth-gen platform around 2040. The design philosophy shares a lot with NGAD, stealth, drone swarming, sensor fusion, and DEW integration. But FCAS is heavily focused on a “system of systems” architecture, where the fighter is just one node in a larger, interconnected web of UAVs, satellites, and ground assets.

Where J-36 Differs

While NGAD and FCAS appear to bet on next-gen propulsion and high-tech sensors, China’s J-36 seems to hedge its bets with brute-force power output. The triple-engine setup may be a necessary move due to current engine limitations, but it also reflects a different risk calculus: prioritize systems integration and operational viability now, even if it means a heavier, more complex platform.

Hence, while the West builds for refinement, China seems to be building for readiness.

The Last Bit, A Glimpse Into the Future of Aerial Warfare

The J-36 may look like an enigma now, tailless, triple-engined, and shrouded in mystery, but it offers a revealing glimpse into China’s strategic mindset. China is willing to bypass traditional design conventions and take technological leaps, even if those leaps come with complexity and risk.

Its three-engine configuration may very well be born out of necessity, compensating for engine power deficits or limited miniaturization, but it also serves a deeper purpose. It signals a desire to power more than just flight: radar systems, energy weapons, electronic warfare, and the nerve center for drone swarms.

In comparison, the U.S. and its allies are walking a different path, leaning on mature propulsion tech, modularity, and long-range planning to produce sleek, highly refined sixth-gen fighters. But refinement takes time. And time, in the volatile calculus of geopolitical rivalry, can often be the rarest commodity.

As the next-gen arms race accelerates, the J-36 stands as a potent symbol of ambition colliding with urgency. Whether it soars or stumbles, the skies of the 2030s will not be ruled by pilots alone, but by the nations that best blend man, machine, and raw power into the ultimate warfighting symphony.

Trump Warns Of Consequences If Nuclear Deal Collapses, Tehran Rejects Direct Talks, Eyes On Israel

U.S. President Donald Trump announced on Monday that the United States and Iran were set to begin direct talks concerning Tehran’s nuclear program. However, Iran quickly contradicted the claim, with its Foreign Minister clarifying that any discussions taking place in Oman would remain indirect.

The conflicting narratives are indicative of the deep mistrust and complex diplomatic discourse that continues to shape U.S.-Iran relations.

Trump, speaking from the Oval Office alongside visiting Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, asserted: “We’re having direct talks with Iran, and they’ve started. It’ll go on Saturday. We have a very big meeting, and we’ll see what can happen.” Without specifying the location, Trump hinted that the talks would be held at a high level and could potentially yield a breakthrough, though he also issued a warning: “If the talks aren’t successful, I actually think it will be a very bad day for Iran.”

Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araqchi, however, countered Trump’s assertion, posting on X that high-level indirect talks would be held in Oman, facilitated by Omani Foreign Minister Badr al-Busaidi. “It is as much an opportunity as it is a test. The ball is in America’s court,” Araqchi stated.

The talks are expected to involve Araqchi and U.S. Presidential Envoy Steve Witkoff. While no immediate agenda has been shared, the discussions will likely center around curbing Iran’s nuclear advancements and easing tensions that have spiked across the Middle East in recent months.

This latest diplomatic overture comes amid a highly volatile regional backdrop – open conflict in Gaza and Lebanon, ongoing military operations in Yemen, a reshuffling of power in Syria, and escalating hostilities between Israel and Iran. Trump, who has significantly ramped up the U.S. military presence in the region since taking office in January, has emphasized that he prefers diplomacy over military confrontation.

Yet, his rhetoric remains sharp. In recent weeks, Trump warned Tehran against defying calls for direct negotiations, even suggesting the possibility of bombing if Iran remained non-compliant. “Iran cannot have a nuclear weapon,” Trump reiterated on Monday, hinting that failure to reach an agreement would bring “great danger” to the Islamic Republic.

Iranian leadership, meanwhile, appears steadfast in its resistance. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who ultimately holds sway over foreign policy decisions, has consistently dismissed direct engagement with the United States as “not smart, wise, or honorable.”

The U.S. and Iran last held direct nuclear negotiations during the Obama administration, which resulted in the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—a multilateral accord that Trump unilaterally withdrew from in 2018. Efforts at indirect engagement under President Joe Biden’s tenure yielded little progress, leaving the fate of any new agreement uncertain.

As talks, whether direct or indirect, prepare to resume under Omani mediation, the world watches closely. With heightened tensions and the shadow of military escalation looming large, the potential outcomes carry significant implications for regional stability and global nuclear diplomacy.

Tehran Rebuffs Trump’s Claim of Direct Talks, Insists on Indirect Path Via Oman Amid Tensions and Diplomatic Chess

Just hours before U.S. President Donald Trump claimed that direct negotiations with Iran on its nuclear program were imminent, Iranian officials reiterated their stance that any forthcoming dialogue would remain indirect – and strictly mediated by Oman.

Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Esmail Baghaei stated that Tehran was awaiting Washington’s response to a proposal for indirect engagement, framing the offer as “generous, responsible, and honorable.” The comments were echoed by a senior Iranian official speaking to Reuters on condition of anonymity, who confirmed, “The talks will not be direct… It will be with Oman’s mediation.”

Oman, which has historically played a discreet yet pivotal role in facilitating backchannel communications between Tehran and Washington, is once again positioned at the center of this delicate diplomatic dance.

In Tehran, skepticism about Trump’s public overtures ran high. Nournews, a media outlet affiliated with Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, dismissed the claim of direct talks as part of a “psychological operation aimed at influencing domestic and international public opinion.”

A second Iranian official hinted at a rapidly closing window of opportunity, suggesting that there may be as little as two months to reach a deal, warning that delays could trigger unilateral military action from Israel. That concern underscores the increasingly high-stakes nature of any negotiations.

Visiting Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, a vocal critic of U.S.-Iranian diplomacy, offered a rare note of conditional support, saying that a diplomatic solution that permanently denies Iran nuclear weapons – akin to the disarmament approach taken with Libya – would be a “good thing.”

During his presidency, Trump unilaterally exited the landmark 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which had curtailed Iran’s nuclear activities in exchange for sanctions relief. He later reimposed sweeping sanctions, leading Iran to accelerate its uranium enrichment well beyond the JCPOA’s prescribed limits.

While Western powers accuse Iran of covertly seeking nuclear weapons capability, citing enrichment levels beyond civilian needs, Tehran continues to assert that its nuclear ambitions are strictly for peaceful energy purposes.

The White House National Security Council declined to comment on the nature of the talks.

This renewed diplomatic maneuvering comes at a moment of severe geopolitical fragility for Iran’s so-called “Axis of Resistance” – a regional alliance built over decades to counter Israeli and U.S. influence. Since the October 7, 2023, Hamas-led attack on Israel, the region has been plunged into instability. Key Iranian allies, Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and the Houthis in Yemen, have faced coordinated Israeli and U.S. military strikes. Last year, Israel also severely weakened Iran’s domestic air defenses, adding to Tehran’s sense of strategic vulnerability.

Meanwhile, the potential collapse of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, another Iranian linchpin in the region, further erodes Iran’s regional clout.

Trump Warns of Consequences if Nuclear Talks with Iran Fail; Reaffirms Strategic Unity with Israel

Amid heightened regional tensions and nuclear brinkmanship, U.S. President Donald Trump met with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to discuss the escalating Iran nuclear issue. Both leaders reaffirmed a unified stance: Iran must never be allowed to acquire nuclear weapons.

While Trump emphasized that diplomacy remains the preferred path, drawing comparisons to the denuclearization process in Libya, he issued a firm warning that failure to reach a deal could trigger serious consequences for Tehran. “Iran cannot have nuclear weapons under any circumstances,” Trump said, hinting at potential military action if negotiations collapse.

The two leaders met in Washington ahead of a high-level meeting with Iranian officials scheduled for Saturday. Trump described the upcoming dialogue as critical, expressing cautious optimism about a breakthrough. “We’re hopeful,” he said, while acknowledging skepticism among observers who believe Iran is unlikely to abandon its nuclear ambitions.

Netanyahu, a long-time opponent of Iran’s nuclear program and an advocate for hardline measures, echoed Trump’s sentiments, stating that while diplomacy is the preferred route, it must lead to a comprehensive and irreversible dismantling of Iran’s nuclear capabilities. He pointed to the Libyan precedent as a potential model for success, provided Iran cooperates.

The conversation between Trump and Netanyahu extended beyond Iran, touching on broader issues of trade, regional security, and strategic cooperation. Trump lauded Netanyahu as “a special person and a true friend of the United States,” reiterating his belief that no U.S. administration has done more for Israel than his own.

This renewed display of alignment between Washington and Tel Aviv comes at a delicate juncture. Iran’s regional influence has been tested in the aftermath of the October 2023 Hamas-Israel conflict, with its proxy network—Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis—facing intensified military pressure. The instability has reshaped regional alliances and brought the specter of a broader conflict ever closer.

The forthcoming talks, which Trump characterized as being held at a “very high level,” are seen as a litmus test for whether diplomacy can still deliver results in a region teetering on the edge. While Iran maintains its nuclear program is for peaceful purposes, Western powers continue to accuse Tehran of advancing toward weapons-grade enrichment, well beyond what is needed for civilian use.

As both Trump and Netanyahu reaffirm their commitment to a peaceful resolution, their statements also reflect a calibrated message: while negotiations are ongoing, time is limited and alternatives are being weighed. With military escalation looming and diplomatic timelines tightening, the latest developments illustrate the fragility of the current geopolitical order. Whether these indirect talks can arrest the spiral toward conflict, or merely delay the inevitable, remains to be seen.

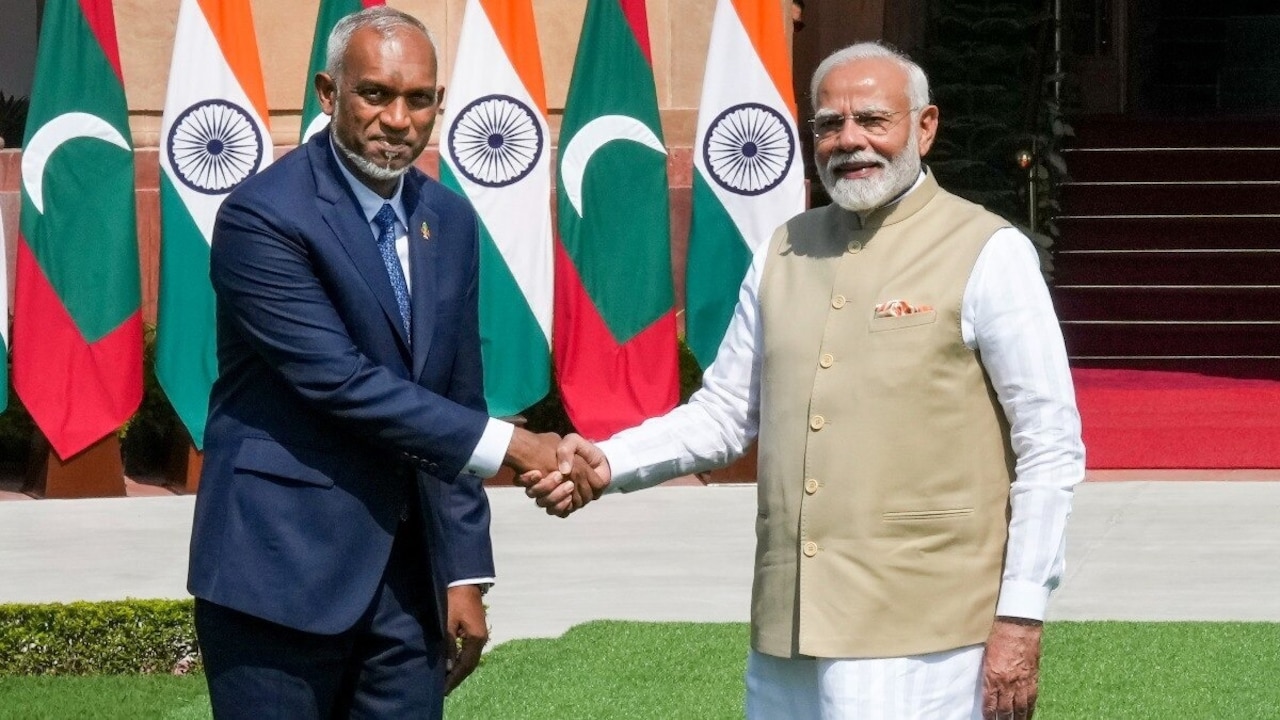

Modi’s Three-Day Visit To Sri Lanka, A Strategic Signal To Maldives—And A Clear Message To China?

When Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi lands anywhere on an official visit, the script is often familiar – tight schedules, brief stopovers, and precision diplomacy. So, when Modi recently spent three days in Sri Lanka, his fourth visit to the island nation since 2019, it raised more than a few eyebrows. Why Sri Lanka, and why now?

To understand the significance, one must look beyond bilateral bonhomie and into the wider geopolitical chessboard, especially the rapidly intensifying great power competition in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), where China has been steadily tightening its grip.

A Visit Laden With Strategic Subtext

Modi’s extended stay was not merely ceremonial; it was deeply strategic. The visit culminated in a host of high-impact Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) across defense, energy, infrastructure, education, and maritime security. While the headlines focused on trade and cooperation, the subtext was unmistakable – India is reasserting its influence in its traditional backyard, and it’s doing so with clarity and purpose.

Among the most pivotal agreements was the inaugural defense pact between India and Sri Lanka. This agreement includes joint military exercises, intelligence sharing, and enhanced maritime security coordination, pillars of what many call “military diplomacy,” a critical tool in India’s Indo-Pacific doctrine.

These are not just friendly naval drills. In the Indian defense establishment, joint exercises are treated as an extension of real war strategy. Coordinated training with Sri Lankan forces enables New Delhi to keep a keener eye on Chinese movements in the Indian Ocean, where Beijing has already invested heavily in ports, logistics, and influence operations.

A Coded Message to Maldives?

The timing also aligns with India’s deteriorated relations with Maldives, a country that has increasingly pivoted towards China over the past two years. While diplomatic silence now prevails between Malé and New Delhi, Modi’s warm embrace of Colombo sends a subtle but unmistakable signal – India has options, and it is prepared to recalibrate its alliances in the region.

As Maldives flirts with Beijing’s orbit, Sri Lanka seems to be anchoring itself closer to India, not just militarily, but economically and energetically as well.

Energy Diplomacy: Powering Influence

India’s energy collaboration with Sri Lanka could become the foundation for a new era of regional energy diplomacy. A joint venture between India’s National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) and Sri Lanka’s Ceylon Electricity Board aims to establish a 120-megawatt solar power plant in Trincomalee—a strategically located area in eastern Sri Lanka where India has long-standing interests.

Additionally, India has committed to supplying LNG to Sri Lankan power plants, despite itself being a net importer, sourcing gas from Qatar, the Gulf, and the U.S.

So why subsidize Sri Lanka’s energy needs?

The answer lies in strategic utility – just as India bought electricity from Nepal and rerouted it to Bangladesh, these actions are geopolitical investments, not commercial transactions. They’re designed to bind regional partners into India’s influence network and reduce China’s strategic elbow room.

Furthermore, plans to establish an electricity grid connectivity system between the two nations will deepen this interdependence and bolster regional energy security – an area where China has also been making significant overtures, especially through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Infrastructure, Capacity Building, and Education: Winning Hearts and Minds

India’s support for rehabilitating Sri Lanka’s railway signaling systems and offering scholarships to 200 students from Jaffna and the Eastern Province are not just goodwill gestures. They are part of a long-term strategy to build people-to-people linkages and soft power. Similarly, training 1,500 Sri Lankan civil servants over five years enhances administrative interdependence and trust.

These may seem like developmental footnotes, but in geopolitics, capacity-building initiatives often yield the most enduring loyalties.

)

China Looms Large

Modi’s visit cannot be de-hyphenated from China’s expanding role in the region. With over 400 MoUs signed with Iran, Chinese access to ports in Gwadar (Pakistan) and potential ambitions in Chabahar (Iran) signal that the Indo-Pacific is becoming a crowded strategic theater. Moreover, with China underwriting Sri Lankan infrastructure – especially the Hambantota Port, now essentially leased to China for 99 years – India is making a calculated counter-move.

China’s increasing sway over Iran also has knock-on effects. Iran, in many ways, is becoming an economic satellite of China. Beijing’s money fuels Iranian projects, its oil supplies China’s growing demand, and its ports offer logistical alternatives to Pakistan. With the Russia–Ukraine war likely to wind down by 2025, and U.S. attention expected to pivot fully towards containing China, India’s moves in Sri Lanka are not just tactical – they are anticipatory.

A Region in Flux, and India’s Game of Chess

Modi’s visit to Sri Lanka was not about headlines. It was about red lines, and making them clear. With China tightening its strategic noose around South Asia and the Indian Ocean, India is shoring up its partnerships, offering not just trade, but trust, not just aid, but agency.

And in the Indian Ocean, where maritime routes are the arteries of global commerce and security, trust and agency might just be the most valuable currencies.

The message to Maldives is clear. The signal to China, even clearer: The Indian Ocean is not open for encroachment without contest. And New Delhi, under Modi, is not watching silently from the sidelines – it’s making its move.

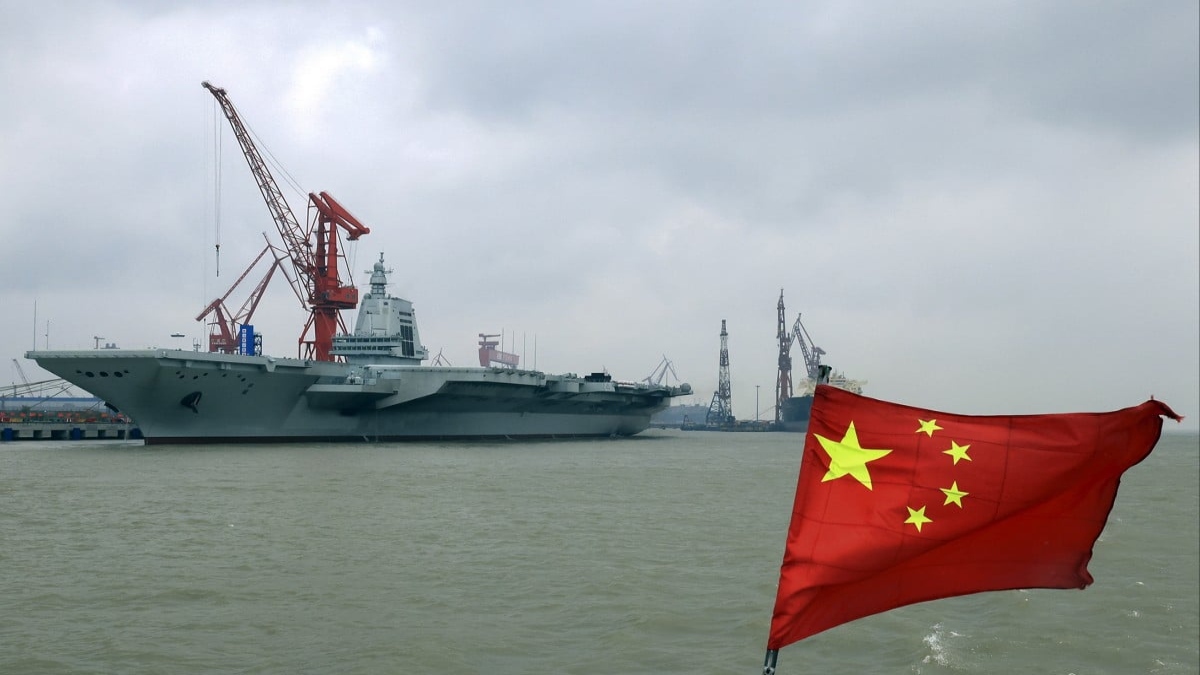

China’s Rise as the leading Global Naval Power

By: Paarvana Sree

China is taking extensive efforts to modernize its Navy. During the 18th Party Congress in 2012, the then President Hu Jintao made a call for China to become a “maritime power” which is capable of safeguarding its maritime interest and rights. President Xi Jinping repeated this position in April 2016 and remarked that “that task of building a powerful navy has never been as urgent as it is today. China’s 2019 defence white paper highlighted the need “to build a strong and modernized naval force” which is capable of carrying out “missions on the far seas”.

The outcome of the modernization of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is an extensive growth in fleet size and capabilities. Research conducted by the leading organisation RAND suggests that China’s surface fleet in 1996 contained 57 destroyers and frigates, but only 3 of these vessels carried short-range Surface to Air Missiles (SAM), making them “defenceless against the modern Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles (ASCM)”.

In the past few decades, China’s navy made a rapid expansion. Around 2015, the Chinese Navy surpassed the US Navy in size and the PLAN made a continuous expansion year since then. The estimates of the US Congressional Research Service reveal that the Chinese Navy consists of 348 ships and submarines in 2021, while the US Department of Defence (DoD) puts the figure slightly higher than 355 vessels. It is to be noted that the fleet sizes of the other leading nations are smaller comparatively. As of 2021, the British Royal Navy consists of 76 ships and the Royal Australian Navy had a fleet of 44 ships.

Between the period of 2017 and 2019, China built more vessels than India, Australia, Japan, France and the UK combined. The vice admiral of Germany Kay-Achim Schonbach said that in 2021 that the Chinese Navy is expanding roughly equivalent to the entire French Navy in 4 years. In 2021, China commissioned 28 ships, while the US could only make 7 ships that year. If China continues to commission the ships at a similar rate, it could have 425 battle force ships by 2030.

According to DoD, a significant intention of the PLAN’s modernization effort is upgrading and augmenting its littoral warfare capabilities, especially in the South China Sea and East China Sea. In response to this China extended up the production of Jiangdao – class (Type 056) corvettes. Since the first being commissioned in 2013, at the end of 2021, approximately 70 types of corvettes have been commissioned. Among this approximately 20 to 22 were transferred to the Chinese coast guard and left 50 to 52 of these vessels to the PLAN. In early 2020, China completed the work on its final type of corvettes 056 and ceased the production to provide attention to advance its blue water capabilities.

It is to be noted that the capabilities of the Chinese Navy are expanding in other areas as well. RAND made a report that, based on the contemporary standards of the ship production for about 70% feet in 2011 is considered to be “modern” from less than 50% in 2010. China is also trying to produce large ships which are capable of accommodating advanced amateur and on board systems. The PLAN’s first type 055 cruisers for example entered service in 2019 and made a displacement between 4,000 to 5,000 tons than the type 052D which entered in service in 2014. The type 055 contains 112 vertical launch systems (VLS) missile cells that can help in area defence while accompanying China’s aircraft carriers in blue waters.

China is also making extensive efforts to build an overall tonnage of new ships that are being put into the sea. The number of ships launched by China between 2014 and 2018 approximately consists of 6,78,000 tons which is larger than that of navies of France and Spain. Moreover the total tonnage of the PLAN remains less than that of the navy of the US. As of 2018, the gap between the two corresponding navies is estimated at roughly 3 million tonnes. The difference can largely be dedicated to the US fielding 11 aircraft carriers, each displaying approximately 100,000 tons.

The growing and rapid expansion of PLAN has been undergirded by China’s growing ship building capability. During the period of the mid 1990s favourable conditions of the market and joint ventures with Japan and South Korea helped China to upgrade its ship building facilities and operational techniques. According to DoD, the expansion of these ship yards has further increased China’s ship building capacity and capability for all types of military projects including submarines, naval aviation and sea lift assets.

These also made China into a commercial ship building superpower. Merchant ship building rose from 1 million gross tonnes in 1996 to 39 million gross tonnes in 2011 which is thrice more than that of Japan in the same year. In 2018 China excelled South Korea to become a global leader in ship building and as of 2020, Chinese ship builders travelled to capture over 40% in the global market in terms of tonnage.

It is to be noted that the same state on companies that dominate ship building industries are also the major players in the military space. Until 2019 China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation (CSIC) and China State Ship Building Corporation (CSSC), China’s two largest ship building companies contained three quarters of China’s overall ship building output. In November 2019, these two major companies merged into a single massive entity, the China Ship Building Corporation also known as (CSSC) which almost accounted for 21.5% ship orders in 2021.

There are basically 6 shipyard spreads across China that fulfils the share of China’s naval ship building needs. These shipyards contain the facilities for producing the commercial vessels. Jiangnan shipyard for instance has produced several type 055 cruisers and it is also responsible for building China’s third aircraft carrier. 20 shipyards are also responsible for delivering one of the world’s largest ethane and ethylene capable tankers. These shipyards continue to build numerous commercial container and tanker vessels.

China’s rapid naval expansion has positioned it as a leading global maritime power, challenging traditional naval dominance in the Indo-Pacific and beyond. With a modernized fleet, aircraft carriers, advanced submarines, and a growing presence in strategic waterways, China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is a key player in global security dynamics. Its naval strategy, bolstered by technological advancements and territorial ambitions, influences geopolitical tensions, particularly in the South China Sea. As China continues to project power, its naval capabilities will shape global maritime security, trade routes, and diplomatic relations, reinforcing its status as a formidable force in international waters.

Build Back Better World: A Vision for the Future

By: Gayathri Pramod, Research Analyst, GSDN

The aspiration to create a better world is not merely a contemporary slogan but a longstanding ambition society has pursued throughout history. From post-war reconstruction and economic revitalization to sustainable development initiatives, humanity has continually sought to establish a more just, prosperous, and resilient global order. This vision holds renewed urgency in pressing global challenges, including climate change, economic disparities, political instability, and technological disruptions. The role of key global players—such as the United States, China, India, the G7, and BRICS—remains instrumental in shaping the world’s trajectory. However, differing interests and strategic approaches often lead to conflicts, making pursuing a truly better world a complex and contested endeavor. One significant initiative addressing global development challenges is the Build Back Better World (B3W) initiative. Introduced by the G7, B3W is designed to promote “values-driven, high-standard” infrastructure development, particularly in the developing world. In response to the mounting infrastructure deficit exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the initiative seeks to mobilize private sector investments across four critical sectors: climate, health security, digital technology, and gender equity and equality. Rooted in the G7’s broader post-pandemic recovery efforts, B3W emphasizes sustainable economic growth, environmental protection, and adherence to democratic values, including freedom, the rule of law, and equality.

If effectively implemented, B3W has the potential to emerge as one of the most significant infrastructure initiatives led by democratic nations. With a broad geographic reach spanning Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and the Indo-Pacific, the initiative strategically assigns each G7 member a regional focus, prioritizing support for low- and middle-income countries. While not explicitly positioned as a direct competitor to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), B3W naturally offers an alternative to the BRI’s vast global network, which connects Asia, Africa, and Europe through the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road. The interplay between these initiatives underscores the broader geopolitical competition shaping the global development landscape and highlights the diverging approaches of leading powers in fostering economic progress and international cooperation. Therefore, through this article, I will explore various facets of Bring Back Better World and its present scenario.

Philosophical Underpinning

The concept of rebuilding a better world has evolved significantly over time, shaped by historical events, economic shifts, and global crises. One of the most significant turning points in modern history came after World War II when the world witnessed large-scale reconstruction efforts to restore economic stability and prevent future conflicts. Among these efforts, the Marshall Plan was crucial in revitalizing war-torn Europe, providing much-needed financial assistance to rebuild infrastructure, industry, and governance systems. The success of the Marshall Plan not only facilitated Europe’s recovery but also strengthened international economic ties and set a precedent for future global cooperation.

Alongside these economic reconstruction efforts, establishing the United Nations in 1945 marked a monumental step toward fostering international collaboration. The UN was founded on diplomacy, collective security, and the prevention of large-scale conflicts. Its creation symbolized a global commitment to resolving disputes through dialogue rather than warfare, reinforcing that a peaceful and cooperative world was possible. Economic institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank also emerged to stabilize economies, promote financial stability, and support development projects in struggling nations. These institutions became key pillars in the global economic order, ensuring that countries had access to financial resources that could help them navigate economic challenges and foster long-term growth.

By the latter half of the 20th century, the focus of global development shifted towards globalization, trade liberalization, and rapid economic expansion. Technological advancements and increased international trade facilitated unprecedented economic growth, lifting millions out of poverty and transforming emerging economies such as China and India into global economic powerhouses. The expansion of multinational corporations, financial markets, and global supply chains interconnected economies in ways that were previously unimaginable. This era of globalization was characterized by economic optimism, with many countries embracing free markets, deregulation, and foreign investments as paths to prosperity. However, despite the benefits of economic expansion, this period also exposed the vulnerabilities of an interconnected world. Economic disparities widened as wealth concentrated in certain regions and among specific populations. Fueled by industrialization and excessive resource exploitation, environmental degradation has become an alarming global issue. Moreover, financial crises, such as the 2008 global economic downturn, revealed the fragility of financial systems and the risks associated with unregulated markets. These challenges underscored the need for a more balanced approach to economic growth, prioritizing social welfare, sustainability, and resilience.

As the world entered the 21st century, it faced various new and complex challenges. Climate change emerged as one of the most pressing issues, with rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and environmental disasters threatening global stability. Meanwhile, digital transformations revolutionized industries, communications, and economies, bringing opportunities and challenges. The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence, automation, and digital finance created new avenues for growth but raised concerns about job displacement, data privacy, and economic inequality. The COVID-19 pandemic further intensified these challenges, exposing weaknesses in global healthcare systems, supply chains, and economic resilience. As nations grappled with the economic and social repercussions of the pandemic, the phrase “Build Back Better” gained prominence, emphasizing the need not just to rebuild but to create a stronger, more equitable, and sustainable global system.

US and China’s role and significance

The United States has historically positioned itself as a global leader in promoting democracy, economic growth, and human rights. The US has played a crucial role in shaping global systems, from spearheading post-war reconstruction to leading the digital revolution. However, in recent years, its influence has been challenged by internal divisions, economic shifts, and the rise of new global players like China. Under the Biden administration, the US has actively promoted the concept of “Build Back Better World” (B3W), a counter to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The B3W aims to invest in infrastructure, climate resilience, and economic partnerships with developing nations, particularly in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. However, the challenge lies in execution, as domestic priorities, political divisions, and financial constraints often limit its global ambitions.

Additionally, the US faces tensions with China over trade, technology, and military influence. While it continues to champion democratic values, its foreign policies sometimes appear inconsistent, leading to skepticism among allies and partners. The challenge for the US is to balance its leadership role while addressing domestic concerns and adapting to a multipolar world.

China’s approach to building a better world is vastly different from that of the US. Instead of emphasizing democracy and human rights, China focuses on economic development, infrastructure, and technological advancements as the primary means of global improvement. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is central to this vision, connecting countries through massive infrastructure projects, trade partnerships, and financial investments. Over the past decade, China has expanded its influence across Asia, Africa, and Europe through BRI, offering an alternative to Western-led financial institutions. While this has accelerated development in many countries, critics argue that it has also led to debt dependency, environmental concerns, and political leverage by China. The growing geopolitical rivalry with the US has further complicated its efforts, as many nations struggle to navigate between the two superpowers. China’s vision of a better world includes technological supremacy, with significant investments in artificial intelligence, 5G networks, and digital finance. However, concerns over data privacy, surveillance, and authoritarian governance have raised global debates on whether China’s model truly represents a better world or a more controlled one. The country’s role in climate initiatives and global trade remains crucial, as its policies significantly impact global carbon emissions and economic stability. China’s economic power has allowed it to create alternative financial institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which competes with Western institutions like the World Bank. However, questions remain over China’s long-term intentions and the sustainability of its investments in partner nations.

India has maintained a cautious stance regarding China’s BRI, viewing it as a strategic challenge rather than an opportunity. While many neighboring countries have embraced Chinese investments, India has opted to strengthen its regional influence through initiatives like the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) and its collaborations with Japan and the U.S. India’s vision for a better world focuses on democratic values, inclusive economic growth, and digital innovation. India is a key player in global development efforts as one of the fastest-growing economies. However, challenges such as income inequality, infrastructure gaps, and bureaucratic inefficiencies continue to hinder its progress. In response to China’s growing influence, India has strengthened its ties with the G7 and BRICS, balancing its partnerships with Western and emerging economies. Its role in climate action, digital governance, and regional stability will be critical in shaping the future global order.

The Group of Seven (G7), composed of the world’s largest advanced economies, has traditionally led efforts in global governance, economic stability, and climate initiatives. However, its influence has been challenged by the rise of emerging economies and shifting global dynamics. The G7’s commitment to rebuilding a better world is evident in initiatives like the B3W and climate action agreements. However, internal divisions, economic slowdowns, and geopolitical uncertainties have made it difficult to implement large-scale reforms effectively. The expansion of G7’s engagement with countries outside its traditional sphere is seen as an attempt to maintain relevance, but skepticism remains about its ability to drive real global change.

On the other hand, BRICS represents a counterbalance to Western-led institutions, advocating for a more multipolar world. The group focuses on economic cooperation, financial independence from Western systems, and technological collaborations. However, internal disagreements among BRICS members and geopolitical tensions, particularly between India and China, have limited its effectiveness as a unified force. The ongoing economic struggles in member nations like Brazil and South Africa have also raised doubts about BRICS’ ability to act as a coherent alternative to Western-dominated financial systems. Despite these challenges, the G7 and BRICS hold significant potential in addressing global issues such as poverty, climate change, and digital transformation. The key lies in fostering greater cooperation, bridging ideological divides, and ensuring that economic growth translates into real social benefits for all.

Bringing back a better world is not a straightforward process. The biggest challenges include geopolitical rivalries, economic disparities, environmental degradation, and technological disruptions. The increasing divide between democratic and authoritarian governance models adds another layer of complexity, making it difficult to establish a universal path to progress. Additionally, global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, financial instability, and regional conflicts have exposed weaknesses in existing systems. The need for a new global framework prioritizing sustainability, social equity, and innovation is more urgent than ever. However, achieving this requires genuine collaboration, responsible leadership, and a willingness to adapt to new realities. While nations like the US, China, and India play key roles, no single country can dictate the future alone. Multilateral efforts through G7, BRICS, the United Nations, and other global institutions must be strengthened to create a more inclusive, fair, and resilient world. Civil society, businesses, and technological innovators must also be part of the process, ensuring that progress benefits not just powerful nations but all of humanity.

The vision of restoring a better world is a historical pursuit and a present-day necessity. From post-war reconstruction to modern economic strategies, the quest for a better world has taken many forms, shaped by geopolitical interests, technological advancements, and social aspirations. Today, as the world faces complex challenges, the role of major global players—whether the US, China, India, G7, or BRICS—has never been more crucial. While their visions may differ, the ultimate goal remains the same: a world that is stable, prosperous, and sustainable for world future generations. The key lies in finding common ground, fostering cooperation, and ensuring that economic and technological progress translates into meaningful benefits for all. The journey may be long and complex, but with strategic efforts and global commitment, a better world is still within reach.

Conclusion

Today, the aspiration to build a better world is pursued through various global initiatives and power blocs, each offering distinct visions for the future. The European Union, for example, has prioritized sustainability and social welfare, implementing policies to combat climate change and promote economic inclusivity. China’s Belt and Road Initiative focuses on infrastructure development and economic connectivity, aiming to enhance trade and economic cooperation across multiple regions. The United States and its allies continue to advocate for democratic values, technological leadership, and strategic economic partnerships to counterbalance emerging global powers. International organizations such as the United Nations, World Health Organization, and IMF also play critical roles in addressing global issues, from public health and poverty alleviation to conflict resolution and humanitarian aid. As the world moves forward, the evolution of the idea of reconstruction continues to be shaped by changing circumstances and new global priorities. The lessons of history have demonstrated that cooperation, innovation, and resilience are essential in navigating the challenges of an ever-changing world. The need for sustainable development, economic inclusivity, and global stability remains at the forefront of discussions on the future of international cooperation. While the road ahead may be uncertain, the commitment to building a more equitable and resilient world drives local, national, and international efforts, shaping human progress for future generations.

One Nation One Election for India: An Idea whose Time has Come?

By: Rishya Dharmani, Research Analyst, GSDN

The prospect of simultaneous elections holds promise for some and peril for others. Supporters argue that it frees democracy from the curse of vested and repeated disruptive electoral cacophony; which breeds corruption, populist offerings, mushrooming costs, and logistical nightmares in organising this gargantuan exercise. Detractors contend that it violates the basic structure by diluting parliamentary democracy and ‘nationalises’ federal politics. Simultaneous elections are not a new concept and are practised in different combinations in Sweden, Germany, Japan, the Philippines, etc. Wider consultations and discussions will conclude whether it is apt and needed in India and in what form.

The Union Cabinet has vetted the recommendations of the High-Level Committee on One Nation One Election (ONOE). The latter had proposed concurrent elections to Lok Sabha and state assemblies in the first phase. Within 100 days, elections will be held for local bodies. In practice, simultaneous elections to Lok Sabha and state assemblies had been a norm in the 1952, 1957, 1962, and 1967 elections. However, rampant abuse of Article 356 led to disruption in several state assemblies’ tenures, and the cycle of the synchronised polls broke. The 170th Report of the Law Commission had maintained that separate elections to states’ legislatures should not be a rule but an exception.

Critics argue that if simultaneous elections are held with 2029 LS polls, then assembly tenures of 17 state assemblies will be curtailed, violating the federal principle that it will undermine regional politics by presidentialising elections, overshadowing local concerns. Coinciding elections till 1967 did not make India a unitary state; on the contrary, it led to better coordination between the Union and states. Some maintain that while regional parties may see a reduced expenditure in the eventuality of simultaneous polls, they may be unable to create discourses making regional demands. The centrist narratives may dominate the political landscape, and local issues may be sidelined, curtailing a pluralist political system. This is disputable as despite the “national wave” favouring the BJP in the 2014 elections, Biju Janata Dal in Odisha increased its vote share from 37% in the 2009 elections to 44% in 2014. Continuous elections one after another may, in effect, foster biases in voter choice, coopting her to choose the party that won the most recent election. Gaps in electoral cycles allow time for introspection and deeper engagement with policy alternatives offered by political parties.

Contrarian research by IDFC Institute on ONOE shows that it induces 77% of voters to select the same party for both state and national legislatures, dropping to 61% if there is a six-month gap between elections. Another fact comes from the Tamil Nadu elections in 1989, 1991, and 1996, when the votes polled by INC and AIADMK differed in state and national elections. In the 2014 Arunachal Pradesh elections synchronised with Lok Sabha parties got different vote shares nationally and in the state. It can be concluded then that electoral fortunes depend on the localised nature of politics, like the presence of alternatives, political contests, voter bribery, and community dynamics, and cannot be generalised. ONOE has the potential to generate a unified and single-minded national resolve on significant issues – a key trigger for the nature and content of third-generation reforms.

Operationalising simultaneous elections would require 18 amendments to existing laws and 13 constitutional amendments. The first constitution amendment bill will deal with the transition to a simultaneous electoral system and the eventuality of premature dissolution of legislatures, which Parliament can pass without states’ ratification. Article 82(A) will be inserted for a fixed five-year term, and another amendment to Article 327. It will discuss the modality of fresh elections for “unexpired term”. The second constitutional amendment will involve panchayat and municipal elections, requiring half of the states’ legislatures’ ratification. There are provisions for preparing a single electoral roll for the entire country and synchronising local bodies’ elections with Lok Sabha and state assemblies. Fixed tenure of five years for Lok Sabha and State assemblies will necessitate amendments to Articles 83, 85, 172, and 174 dealing with the duration and dissolution of two legislative bodies. Article 356 would also need to be amended.

The debate over the cost of election vs the cost of democracy is raging in this context. The Election Commission has called Indian elections the “largest event management exercise on earth during peacetime”. Expenses ranging from voter outreach events, star campaigners’ expenditures, personnel costs, etc., have ballooned legally reported election-related expenses, with almost 3-4 times the amount spent in the parallel black economy. EC has calculated that ONOE can be conducted in US$ 79.5 billion. In perspective, the 2024 Lok Sabha elections cost more than US$ 1000 billion approximately, whereas the combined US presidential and Congressional elections cost US$ 6.5 billion in 2016. However, a counterargument states that EC would need to simultaneously arrange 2.5 million EVMs and VVPATs (currently possessing only 1.2 million) for streamlined polls.

Some contend that elections are the lifeblood of democracy, and their value cannot be judged by the once-in-a-five-year expense they generate. However, taxpayers’ money can be diverted towards much more virtuous developmental goals promising substantive welfare more than procedural satisfaction of a successful election. Given the precarious nature of the external security situation with a simmering two-front war – India’s defence expenditure as a percentage of GDP clocked less than 2% in the 2025 Budget. Even internally, a continuous cycle of elections incentivises political parties to foster a bureaucratic-politician nexus to recover money spent on recurrent elections via corruption and black money, hurting the prospects of the real economy in the long run. Some allege that public works are virtually suspended during the electoral heat, resulting in a monumental waste of government resources.

Till 2021, the country experienced elections of 2-5 state assemblies every six months. Repeated promulgations of the Model Code of Conduct suspend major developmental work and welfare schemes, as noted by the Parliamentary Standing Committee’s 79th Report. ONOE will nip policy paralysis in the bud, producing less disruption of everyday public life due to road shows, noise pollution, and paper waste through campaigning material. It will ensure the stability and predictability of programmes with policy continuity. Otherwise, the current system predisposes the political class to opt for safe and revadi policies, avoiding politically risky, unpopular transformational change. Fixing “full term” at five years will encourage long-term visionary policy-making, deepening representation, and truly enabling elections as a “festival of democracy”.

It is well-known that Indian elections tend to be a spectacle of larger-than-life political drama and high-decibel knockouts. For months altogether, all elements of public life (from boardrooms to drawing rooms) are consumed in this tamasha – imperilling the cause of good governance. If we were to look at this issue from the perspective of human security, then we would find that the mammoth expense (including black money), a stranglehold on public life and raucous disruption of civility in campaigning necessitate some level of simplification and pruning of electoral process. ONOE (with some modifications) seems apt to sanctify the conduct of elections. The threat of ‘presidentialising’ of the electoral outcome is present in the current scenario. However, with concurrent polls, critics point to the ’subservience’ of state legislatures to the term of Lok Sabha, while constitutionally, this hierarchy is unacceptable. Policymakers need to be cautious of fomenting federalist dissensions on this front and need extensive consultations to resolve these cracks in the proposed format of ONOE.

Reduced accountability is possible as artificially fixing rigid electoral cycles impinges on voter choice and lessens democratic will. A parliamentary system is founded upon executive responsibility to legislature, which will be compromised if fixed tenure is imposed. Since the 1951 elections, 60% of Lok Sabha MPs were never re-elected to the lower House after their first term ended, signalling that irrespective of the tenures of legislatures, accountability to the electorate is strong in India. The High-Level Committee has proposed that in case of the dissolution of the legislature prematurely, another election is proposed to be conducted for an “unexpired term.” By-elections will be clubbed together and held once a year. In the event of loss of confidence, midterm elections will usher in a new government for the remaining term, for which voters may find fewer stakes to vote or less incentive for contestants to stand in the poll fray.

One way to deal with this conundrum is to hold simultaneous elections in two phases; if the

assembly or Lok Sabha gets dissolved mid-way, then EC can coordinate elections with the next phase for the remaining term, or if less tenure remains, then president rule can be imposed. The goal is to quell voter fatigue stemming from repeated elections and reduced turnout in elections that are held later. In Sweden, elections towards Riksdag (parliament), county council assemblies and municipal councils take place on the same day – saving valuable time and effort for voters, candidates and polling officials. To quell the premature dissolution of assemblies, the German model of a constructive vote of no confidence can be adopted to dissuade factionalism and horse trading from toppling governments.

Concurrent polls also offer rationalised security forces deployment, who otherwise are diverted from their core competency year-round to man electoral booths. A counterargument is that simultaneous elections will demand huge manpower to be utilised simultaneously, creating an opportune moment for security risks as 4,719 companies of CAPFs. EC would need to secure an additional 2.6 million ballot boxes and 1.8 million VVPATs. The issue of harmonising elections with geographical, weather, cultural (festivals), and security challenges is also noted. And yet, the Indonesian experience of the world’s largest single-day election, with Presidential, Vice Presidential, Parliamentary, Regional Assemblies and Municipal elections on the same day, indicates that it is possible to smooth over logistical roadblocks. The 2024 Lok Sabha election saw more than 600 million voters exercise their franchise, while the European Union has only over 400 million registered voters. Managing the world’s largest electorate is a humongous task, but EC is more than competent in evolving SOPs with trial and error.

The report of the 22nd Law Commission should be awaited in this regard. Concerns of regional parties and some political activists on ONOE should be given due importance. EC can also consider reducing electoral phases to reduce expenditure and maintain voting momentum. Further, as in Sweden, fixed dates can be announced for Parliamentary and municipal elections for predictability in election management. A modified version of ONOE, where the country could be divided into zones for electoral purposes, will stymie the regional concerns of centrist forces usurping the agenda as local issues will remain in the fray. The way forward is to host a broader debate within the parliament and civil society on ONOE.

From a strategic perspective, ONOE impacts the federal relationship between the Union and states – whether this mock unification of polling cycles can produce the consciousness of programmatically aligned and purposive governance is a moot question By, proposing to rationalise expenditure and other human and material costs – it favourably disposes the exchequer to allocate the said funds on capex and other prudent heads. The predictability of elections also lessens the volatility of stock markets and opportunistic fluctuations in capital markets. Take the case of Belgium, where the parliamentary elections are held every five years in tandem with the European elections- and this periodicity flushes out possibilities of bad actors manipulating outcomes due to the foreseeability of the electoral timetable. It also helps the stakeholders to plan their electoral strategies in time adequately.

There are also fears that the ONOE can translate into ‘one voice’ – since if the national legislature collapses, state assemblies would likewise dissolve, thereby contravening the federal principles. This and other lacunae of the Indian electoral system, including defection and horse-trading, can be curbed by the German example of ‘constructive no confidence’ motion. However, due to fracas raised on some disconcerting points – the government must provide clarity and tread the path of wider consultations on the prospect of simultaneous elections. The argument that separate elections enable regional politics to thrive and that ONOE risks binding India into artificial synchronicity is worth pondering. Given that India currently has a thirty-year window to race up towards Viksit Bharat status – we cannot afford to have fundamental divergences such as these, as a sound electoral system is the foundation for a stable and visionary political leadership.

Strong India-Azerbaijan ties will Benefit both Nations

By: Sonalika Singh, Research Analyst, GSDN

In the context of an increasingly interconnected world, the significance of bilateral relations between countries cannot be overstated. One such example of potential for growth and cooperation lies in the burgeoning relationship between India and Azerbaijan. These two nations, despite being geographically distant, share a multitude of interests, values, and strategic objectives that can contribute to building a strong, mutually beneficial partnership.

India, the world’s largest democracy and one of the fastest-growing economies, stands at a crossroads in terms of its foreign policy and global partnerships. As it looks to expand its presence and influence in global affairs, strengthening ties with nations like Azerbaijan offers a strategic opportunity. Azerbaijan, located at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, is a key player in the South Caucasus region, strategically positioned at the intersection of major energy routes and geopolitical interests.

Both nations, though different in size, history, and geography, find in each other a valuable partner capable of driving long-term collaboration across various domains. From energy cooperation to trade and strategic alliances, the India-Azerbaijan relationship has vast potential for mutual benefit.

India and Azerbaijan enjoy warm relations, rooted in civilizational linkages, cultural affinities, and shared values of understanding and respect for one another’s cultures. The Ateshgah fire temple near Baku is a prime example of the long-standing historical relations and cultural exchanges between India and Azerbaijan. This 18th-century monument, with an even older history, features wall inscriptions in Devanagari and Gurmukhi. It serves as a lasting testament to the trade links and hospitality enjoyed by Indian merchants traveling along the Silk Route to Europe, particularly in Azerbaijani cities such as Baku and Ganja.

The cultural exchanges over ages between Azerbaijan and India have led to close cultural affinity and shared traditions. World renowned Azerbaijani poet Nizami Ganjavi had a profound influence on eminent Indian poets like Amir Khusrau. In recent past, the famous Azerbaijani artist, Rashid Behbudov, a noted tenor who switched to singing popular Azerbaijani songs in European classical tradition, was a close friend of late Raj Kapoor. Indian intellectuals like Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore are well known in Azerbaijan.

During the period when Azerbaijan was part of the former Soviet Union, India’s Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore, former President Dr. S. Radhakrishnan (as Vice President in 1956), and former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru (in 1961) visited the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic.

India recognized Azerbaijan as an independent country in December 1991 and established diplomatic relations in February 1992. The Indian Mission in Baku was opened in March 1999, while Azerbaijan opened its resident mission in New Delhi in October 2004.

Former Vice President of India, Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu, visited Baku for the NAM Summit from 24-26 October 2019, accompanied by External Affairs Minister, Dr. S. Jaishankar. More recently, Dr. Jaishankar met Azerbaijani Foreign Minister Jeyhun Bayramov on the sidelines of the 19th NAM Summit in Kampala in January 2024. Former External Affairs Minister, Smt. Sushma Swaraj, visited Azerbaijan in April 2018 to attend the NAM Ministerial Conference and for a bilateral visit. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi participated in the online NAM Summit on the theme “United against COVID-19,” held at the initiative of Azerbaijani President on 04 May 2020. Anupriya Patel, Minister of State for Commerce and Industry, visited Baku for the 6th meeting of the Inter-Governmental Commission on 25 October 2023.

Several ministerial-level visits from Azerbaijan to India have taken place since 1991. Deputy Foreign Minister Mr. Elnur Mammadov visited India in November 2022 for Foreign Office Consultations and again in March 2023 to participate in the Raisina Dialogue. Deputy Minister of Economy Mr. Sahid Mammadov visited India to participate in the Vibrant Gujarat Summit in January 2019. Mr. Mukhtar Babayev, Minister of Ecology and Natural Resources, visited Delhi to attend the 5th Inter-Governmental Commission in October 2018. Mr. Samir Sharifov, Minister of Finance, visited India in February 2018. Mr. Nagif Hamzayev, Member of Parliament, visited India under ICCR’s Distinguished Visitors’ Programme in August 2019.

In June 1998, the two countries signed an agreement on economic and technical cooperation, and in April 2007, they signed a deal to establish the India-Azerbaijan Intergovernmental Commission on Trade, Economic, Scientific, and Technological Cooperation. This marked the beginning of a stronger and more meaningful relationship between the two nations, creating new opportunities for cooperation and mutual benefit. However, in recent decades, China’s growing influence in Eurasia and the ongoing hostility between India and Pakistan have hindered India’s efforts to establish direct connectivity for robust trade and economic relations with the region.

To overcome these obstacles and revive its historic relationship with the Caucasus region, India has pursued several connectivity projects. In 2002, India, Russia, and Iran signed an intergovernmental agreement to construct the 7,200-km International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a multimodal transport route that includes sea, rail, and road links connecting Mumbai (India) to Saint Petersburg (Russia) via Iran. India has also invested heavily in the Chabahar Port in the Iranian province of Sistan-Balochistan. However, these initiatives have faced delays due to investment challenges following renewed US sanctions on Iran, inter-regional disputes, and bureaucratic hurdles for certain projects, such as the 628 km-long Chabahar-Zahedan railway line and the 164 km Rasht-Astara railway line. Nevertheless, in July 2022, the INSTC recorded its first shipment from Russia’s Astrakhan Port to India’s Jawaharlal Nehru Port.