Global Strategic and Defence News (GSDN) started its foray on November 11, 2022 as a forum to provide accurate analysis on geopolitical and defence issues that concern the world at large

Land Warfare in the Anthropocene: Ecological Constraints on Future Indian Military Operations

By: Taha Ali

At a breathtaking pace, climate change is reshaping battlefield environments, becoming a threat multiplier that we need to center on in military strategic thinking. India is a land of environmental variability; bordered by glaciated mountains, deserts, and monsoon-fed plains that is already lurking in their face is the consequential environment encountered in the Anthropocene directly related to land warfare. The increased Himalayan glacial melting, accelerating desertification of the Thar, and the lethal concoction of heat-ravaged land and flooding of central and eastern India are threatening to become not far-off futurist writing scenarios, but instead are already impeding deployment cycles, movement, logistics, and sustainability of forward operations. In thinking about the future of the military in a climate-affected context, India’s military will have to consider the strategic frame long term and bring an overall understand of ecological constraints into thinking about national security analysis and operational axioms. The Anthropocene lens applied to conflict analysis is not episodic reversal, it is a change of structure one that requires militaries to rethink not just how they undertake combat but perhaps where, when, and with what costs.

Himalayan Retreat and Desert Advance: Terrain-Driven Disruptions

The Himalayan-dominated north border is India’s most strategic military region, but it is also one of the most environmentally sensitive. Thawing glaciers due to a rise in temperatures are causing unseasonal flows of water, flash floods, and landslides in areas like Ladakh, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh. In Ladakh, soldiers stationed along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) have had to deal with roads swept away by glacial lake outbursts and monsoon rains that cause landslides. In 2025, the Chaten landslide in Sikkim destroyed an army outpost and showed just how much intensity in the monsoons and fragility of terrain now vitally erode military preparedness. Repair work in its wake took weeks both because of the logistical challenges as well as continuing inclement weather.

This environmental unpredictability is compelling a reimagining of the maintenance of forward deployments. Lines of logistics are becoming more fragile—convoys are abandoned, bridges get washed out, and airstrips experience weather-related disruptions. The traditional seasonal war-fighting logic of winter fighting and summer preparation is being reversed by climatic aberrations. Monsoons are lasting longer and falling more unpredictably, with winters growing milder in some regions, upsetting scheduled windows for operation and maintenance. In some industries, this unpredictability actually cripples the rotation schedule of troops, adding to physical and psychological fatigue. At the same time, in India’s western deserts of Rajasthan, it is the reverse: creeping aridity. Although periodic monsoon greening created an illusory appearance of fertility, satellite imagery and ecological surveys affirm that the Thar Desert is growing, advanced by soil erosion and dune movement. The outcome is accelerating water shortage, record summer temperatures in excess of 50°C, and frequent sandstorms that clog machinery and drain troop reserves. Patrols along the India-Pakistan frontier become increasingly hemmed in by these circumstances, with diesel convoys carrying water and fuel becoming more vulnerable and more essential than ever. If the desert becomes more fluid, with roads and outposts being engulfed by dunes, then India will be compelled to rethink how it can project a viable presence in this unruly and growing area. Already, remote sensor and drone surveillance are becoming a replacement for round-the-clock manned presence in some sections, a trend set to gain momentum in the years to come.

Climate Pressure on Logistics, Doctrine, and Technology

From the Indo-Gangetic plains to the northeastern floodplains, climate change brings a two-edged crisis: intense heat and severe precipitation. In Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Assam, prolonged stretches of dry, oppressive heat are followed by deluges that overwhelm civilian and military infrastructure. In 2024, the Northeast experienced several deadly landslides and floods that displaced thousands, bringing both humanitarian relief and military logistics to a standstill. Severe weather is as much a constraint in Indian defense planning as terrain or hostile fire. Military bases along flood-prone locations like Tezpur and Guwahati are spending on flood protection mechanisms, but these are still reactionary rather than anticipatory adjustments. This renders mobility and logistics the weakest links in India’s strategic chain. Road and rail networks critical for resupply can be knocked out or made useless for weeks. Heatwaves impair machines, lower the endurance of troops, and present lethal health threats. These stresses require innovation: the Army will have to transition to more autonomous logistics (unmanned resupply vehicles and air drones), spend on climate-resilient infrastructure, and build module-based, energy-independent forward posts with solar and wind power. Positively, the Indian Army has already started employing solar panels in certain outposts on the border and the Air Force has experimented with biofuels in transport planes. These are encouraging moves towards less reliance on fossil fuel convoys, not only vulnerable to attack but ever less viable in a hotter planet. Other technologies like mobile desalination plants, water-from-air machines, and hybrid-power battle vehicles could increase operational independence.

Tactics and training need to adapt as well. Heat acclimatization and flood response training should be fundamental competencies in every unit. Heavy armor divisions might be forced to rethink their role in marshy terrain or soft desert conditions, while lighter and more agile units supported by airlifts will prove invaluable. In addition, the Armed Forces need to establish institutionalizing climate risk into strategic thought. The Land Warfare Doctrine (2018) and Joint Doctrine (2017) mention environmental factors cursorily at best. A doctrinal revision must acknowledge that environmental degradation is central, not peripheral it dictates when and where soldiers can engage, how long they can remain supported, and what equipment they will require to survive. A new “Green Doctrine,” combining sustainability, resilience, and agility into planning constructs, could inform this transformation.

Conclusion

Climate change, as part of a planetary emergency unfolding at a rapidly increasing rate, has altered the battlefield almost instantaneously, is now becoming a threat multiplier and is what we need to concentrate on in military strategic thinking. India as an eco-strategic space surrounded by glaciated mountains, deserts, and monsoon-fed plains that are being increasingly scrutinized both by military planners and climate scientists alike, already has a consequential environment encountered in the Anthropocene in relation to land warfare. The increasing glacial melt in the Himalayas, desertification of the Thar, and lethal combination of heat-cursed land and flooding in central and eastern India have already begun to reach the point where they may no longer be futuristic writing scenarios, but instead already present severe limitations on deployments cycles, movement, logistics, and sustainability of forward operations. In considering a future for (Indian) military forces in a climate-affected context, military planners will ideally have to consider the longer term strategic frame and build in a more complete recognition of ecological constraints to the overarching national security analysis and operational axioms. The Anthropocene lens applied to conflict analysis is not an episodic change, but a structural change, a new structure that requires militaries to rethink not just how they conduct combat, but maybe where,

Additionally, India also must engage with its regional partners including Bhutan, Nepal, and Bangladesh—to address shared environmental security risks that cross borders. Sharing hydrological data, disaster response coordination, and environmental intelligence will be essential for creating a stable military ecosystem in South Asia. If the Armed Forces can adapt to grapple with climate change the approach will ensure operational readiness while enhancing national security in its broadest definition. In the Anthropocene, adaptability is not just about tactics but it is also about strategy as the next battle space will be created not just by adversaries, but by a planet whose environment is changing rapidly.

Has USA Re-Emerged as the Key Player in the Middle East?

By: Namya Sethi

The Middle East is still enormously significant to world politics because it has a lot of oil, is the birthplace of three major religions (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism), and has a long history of violence and political instability. The United States (US) has had a large effect on the region’s politics and security in the last few decades because of its military activities, diplomatic efforts, and strategic partnerships.

A lot of people felt the US was drawing back from its large involvement in Middle Eastern problems after being active in Iraq for a long time (2003–2011) and Afghanistan for a long time (2001–2021). Recent events, on the other hand, show that the return is more balanced and built on diplomacy, cooperation, and partnerships with more than one country. On the other side, China and Russia are gaining power by striking deals in defense, energy, technology, and infrastructure. Because of this, peace in the Middle East is a concern for the whole world, not just the Middle East.

As a college student majoring in sociology, I believe this is a significant period. We need a nuanced and multi-faceted approach that involves diplomacy, development, and respect for local voices, as well as hard power, to bring peace to the Middle East.

Historical Background

The US became more active in the Middle East after World War II. Washington helped build Israel in 1948 and made strategic alliances with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries. During the Cold War, the US fought against Soviet power. But the biggest change happened after the attacks on September 11, 2001, when the US initiated the Global War on Terror and invaded Afghanistan in October 2001 and Iraq in March 2003.

These actions were originally supposed to stop weapons of mass destruction and break up terrorist networks. However, they swiftly developed into long, costly occupations.

The region was in chaos for a long time after groups like the Taliban and Saddam Hussein’s government were destroyed because of the instability and insurgencies that followed.

People in the US and the Middle East were tired of the military being there all the time by the middle of the 2010s. As Washington began to withdraw from direct engagement, other nations, notably Russia, Iran, Turkey, and China, assumed the power vacuum.

The Trump Years (2017–2021)

President Donald Trump’s foreign policy changed a lot about how the US worked in the area. The US left the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), generally known as the Iran Nuclear Deal, on May 8, 2018. This put Iran back under harsh sanctions. The decision was controversial, which made many angry and led to clashes in the region.

Trump also helped make the Abraham Accords, which were signed in September 2020. These accords made relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco normal. These agreements were a huge change since they demonstrated that certain Arab countries were willing to talk to Israel diplomatically, even while there was no progress toward Palestinian statehood.

Critics, including me, recognized that the Accords were a diplomatic success, but they weren’t sure if they would continue without a complete peace process that includes Palestinians. The Trump administration also skipped established multilateral forums, which made it look like they were more interested in short-term deals than long-term growth.

Biden’s New Plan

Joe Biden promised to bring back diplomacy and multilateralism when he became president in January 2021. His government tried to make friends again while also reducing back on direct military action. After the failed withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021, the US sounded cautious but set on changing how it was involved in the region.

Instead of sending soldiers, Biden prioritized humanitarian aid, working together in the region, and diplomacy. His government offered more money to United Nations (UN) humanitarian efforts in war-torn areas and began talking to Iran and its neighbors again. The US began to speak more openly about safeguarding civilians and human rights, but it still had strong ties to Israel and the Gulf states.

Reestablishing a Presence in 2025

It was evident by the start of 2025 that the US was going to get back involved in the Middle East with a new plan. In March 2025, Houthi insurgents attacked commercial ships in the Red Sea, which caused a coordinated response. The USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) from the US joined French and Egyptian naval soldiers to protect global trade channels and stop additional attacks.

This marked a shift from acting alone to cooperating with regional and international partners on joint efforts. The emphasis on protecting trade and maritime infrastructure demonstrated that America sought peace through stability rather than conflict.

Help for persons who need it and safety for civilians

The US committed to provide Gaza US$1.2 billion in humanitarian aid on May 16, 2025, after things became worse. The support, which was delivered with the help of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), focused on food, housing, clean water, and emergency medical care.

The US aid proposal plainly indicated for the first time in years that it would safeguard civilians no matter what their political opinions were. The US was still firmly on Israel’s side, but it was open to diplomacy that balanced humanitarian concerns with strategic ones.

Reevaluating Military Aid to Israel

Reports that came out in June 2025 indicated that US-made weapons were used in populated civilian areas in Gaza. This made both sides of the aisle in the US Congress upset, which led to hearings on how to keep an eye on military spending. Civil society groups wanted all arms transfers to be linked to requirements for human rights.

The Biden administration stated it still supports Israel, but it also promised to be more open and watch things after the sale. The argument marked a turning moment that made ethics and responsibility important parts of foreign military policy.

Iranian diplomacy

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) fell apart, although talks with Iran started up again in Vienna in early 2025. The US, European Union (EU), and regional powers talked to each other to try to block Iran from gaining nuclear weapons and to stop cyberattacks and proxy conflicts in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.

Although progress is still gradual, the talks suggest that people are starting to believe in working together again. This is really crucial for a student. Talking, even if it doesn’t help right away, builds trust and keeps problems from getting worse.

Military exercises and working together

There are around 30,000 US troops in Bahrain, Qatar, Iraq, and Kuwait. The US and Jordan staged significant joint drills in May 2025 that focused on battling terrorism, regulating borders, and sharing information. This kind of cooperation is very crucial since cells connected to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) are coming back.

These drills are different from earlier campaigns because they focus on giving local forces the tools and training they need to keep the peace.

Working together in business

In 2025, the shift to economic diplomacy was a huge change. In April 2025, the US and Iraq made a US$2.5 billion contract to aid with solar energy, fix up Mosul’s public schools, and make the area’s health care better. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is carrying out US-backed reforms in Lebanon to stabilize the banking sector and restore basic services.

Things that cause conflict, such as not having a job, not having enough money, and not being able to receive an education, are what economic development is all about. The change from bombs to budgets shows that peace must be built from the ground up.

Soft Power and Programs for Young People

The US is still putting money into soft power. Educational programs like the Fulbright Program helped regional scholarships expand by 30% between 2015 and 2025. Two universities that bring people from diverse cultures together are New York University (NYU) Abu Dhabi and Georgetown University in Qatar.

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) pays for projects in Tunisia, Morocco, and Iraq that promote women’s rights, literacy, and entrepreneurship. These programs help people get to know one another better and make connections that last by treating each other with respect and working together to make progress.

Public Opinion and Civic Engagement

Even if the US works with several Middle Eastern regimes, a lot of people in those nations still don’t trust the US. In May 2025, people in Beirut, Amman, and Baghdad started to protest peacefully. People who were protesting wanted foreign aid to be more open and local governments to have more power to make decisions.

From the point of view of young people and students, these voices need to be heard. To bring peace to the Middle East, people in different communities and countries need to talk to one other.

The Future of Technology and New Ideas

Digital cooperation is a new area to explore. In 2025, tech leaders and think tanks in the US started talking to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) about how to control artificial intelligence (AI) and cybersecurity. People are still talking about formal treaties, but early exchanges suggest that innovative diplomacy will play a significant role.

If we give power to regional businesses, promote smart infrastructure, and make sure that digital ecosystems are safe, the area could change. Investing in fresh ideas helps the economy stay strong now and in the future.

The Role of Multilateral Institutions

The US is depending more and more on multilateral groups like the United Nations (UN), the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to advocate for sustainable development and call for reforms in how countries are run. In nations that aren’t stable, like Yemen and Lebanon, cooperative initiatives help keep an eye on corruption, support elections, and send help in times of need.

This multilateral method makes sure that many countries work together to keep the peace, not just one big one.

The Media’s Part in Cultural Diplomacy

American culture is still quite popular over the world. In March 2025, the US Embassy in Amman organized a celebration for cultural interaction. Over 40,000 people came to see Arab student poets and American jazz musicians. Even though these moments are symbolic, they help people comprehend each other and get rid of their biases.

Media projects financed by the US also help young journalists in the area battle extremist propaganda and encourage free expression.

Issues with security and ethical leadership

The US still has to figure out how to balance its moral duties with its military ones. A new rule passed by the US Congress in June 2025 said that weapons had to be tracked after they were sold and that the people who used them had to be checked. This makes sure that guns aren’t used against people who aren’t involved in crime or violence. This is part of a wider shift in US foreign policy, from controlling to working together and from dominating to conversing.

The law is a huge change that signals that arms deals will be more open and fairer. It addresses global concerns about fatalities and the misuse of U.S.-supplied armaments. Instead of extending the fight by giving the military too much freedom, the U.S. aims to restore confidence, obey international law, and help rebuilding efforts by tightening monitoring.

Conclusion

As of June 2025, the United States is at a crossroads in the Middle East. The country is no longer known for invading and occupying other countries. Instead, diplomacy, humanitarian action, economic investment, and cultural involvement define it. We can’t make peace in the Middle East; we have to work together to make it happen. The greatest way to move forward is to provide power to local communities, put money into education, support an honest foreign policy, and make civil voices heard.

As a sociology student, I believe that the US has the ability and the opportunity to be more than just a superpower. It may also be a good partner in making the Middle East a safe place to live by being accountable, responsive, and polite. For this transition to happen, we need to move away from policies that are all about power and toward ones that are all about people. The United States should support grassroots initiatives to promote peace, put human rights first in its relationships, and advocate for inclusive governance in the region. Long-term peace can only happen when foreign policy is based on what average people desire, not just what is best for the country. By listening, learning, and leading with kindness, the United States can help make the world a better place.

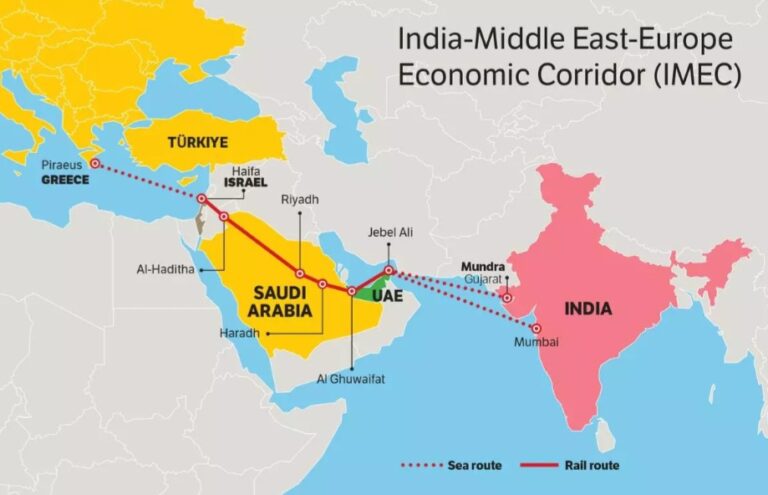

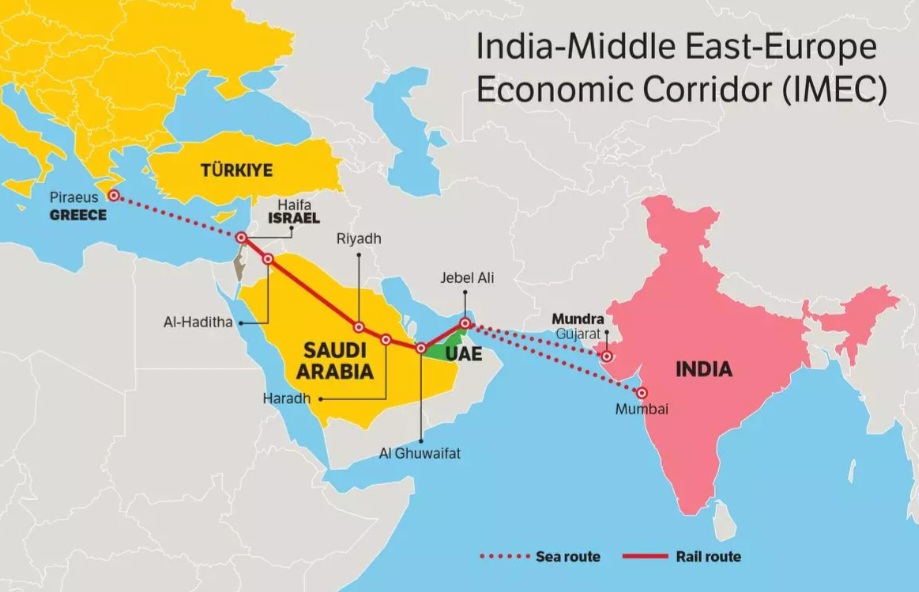

Is IMEC a Casualty of the Middle East Tensions?

By: Simran Sodhi

It would be an appropriate assessment to make at this point that one of the biggest casualties of the Israel-Iran conflict is likely to be the ambitious India-Middle East- Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). The project was announced on the side lines of the G20 Summit held in September 2023 in New Delhi and aims to connect India to Europe via the Middle East with ports, railways and roads. Many analysts point out that the IMEC will challenge China’s Belt and Road Initiative, when completed, and that is also the reason why the United States had backed the project with great enthusiasm (but so far has not committed any funding for the project). 2023 was the time when Joe Biden was President of the US and had backed the project, but with President Donald Trump at the helm of affairs now, that is yet another unpredictability in the project taking off.

The proposed corridor will link India to Europe via the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Israel and Greece. First it was the Israel-Gaza conflict that changed the equations between the Middle East and Israel. The 2020 Abraham Accords, wherein UAE normalized relations with Israel followed by Morocco, was seen as a watershed moment in Middle East politics. It also saw Saudi Arabia moving forward to recognising Israel, prodded by the US that it would provide the Saudis security assurances in return for recognizing Israel. All that changed on Oct 7, 2023 with the horrific attack by Hamas. And as Israel continues to bomb Gaza in an unrelenting fashion, all deals seem off the table. And now with the heightened tensions between Iran-Israel, the fate of IMEC is more uncertain than ever before.

Economics and politics are deeply intertwined and nowhere is this more obvious than in the ambitious IMEC project to link continents. As the political situation changes and Iran-Israel tensions peak, with Gaza already in the middle of a humanitarian crisis, it will become difficult for the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Jordan to promote any economic activity that links them to Israel. It is also to be noted here that this becomes more problematic in Jordan where most of the kingdom’s population is ethnically Palestinian, including Queen Rania.

The Middle East, since 2023, seems to be in a constant state of tensions that show little sign of an early resolution. Iran today, even after the US bombing and its recent war with Israel, seems to be standing tall and reports suggest little or no damage to its nuclear capabilities. It’s proxies like Hamas and Hezbollah in Lebanon have nevertheless been weakened to a great degree. For Iran, this is also an opportunity to take a leadership role in the region and push the Saudis down a bit on the rung. IMEC is also going to get affected in the context here that the Saudis can ill afford an impression both domestically and in the Middle East region that they failed to stand by the Palestinians. And with the Saudis not wanting to go ahead with recognizing Israel, and then not wanting to get into deeper economic ties with Israel, IMEC will have trouble taking off. It would be a safe bet to state at this point that even if IMEC eventually does take shape, it is unlikely to happen as long as this conflict and humanitarian crisis continues.

After the Oct 7 attack by Hamas, former US President Joe Biden had twice said that he was convinced that IMEC is one of the reasons why Hamas attacked Israel. “I’m convinced one of the reasons Hamas attacked when they did, and I have no proof of this, just my instinct tells me, is because of the progress we were making towards regional integration for Israel, and regional integration overall. We can’t leave that work behind,” he said. There is little doubt in most people’s minds today that the attacks by Hamas was meant to bring world attention back to the Palestine cause, and to stop Saudi Arabia from going forward with recognising Israel since this regional economic integration would have brought Israel closer to UAE and Saudi Arabia.

So, in the short term, it would be a fair point to make that as long as the crisis in Gaza continues and the Israel-Iran tensions dominate the regional politics, one should expect UAE and Saudi Arabia to focus more on their inter-connectivity projects. India can always be included in those equations but the inclusion of Israel is difficult. Saudi Arabia has said repeatedly that there can be no recognition of Israel without a Palestinian State. So IMEC is likely to be a limited project going forward, contrary to the grand ambitions with which it was launched. Once things return to a new normal, we might see IMEC and its related projects take off but as of today, this will remain on the backfoot for most member states.

Why Hard Power Only Matters?

By: Lt Col JS Sodhi (Retd), Editor, GSDN

Thucydides, the famous Greek historian’s quote in 430 BCE “The strong do what they have to do and the weak accept what they have to accept” is as relevant in today’s era as it has always been centuries down the line. There is no period in world history which has seen total peace, and neither there will be any in the near future.

History has proven that only the strong have emerged victorious and hard power has been the only major deciding factor. As “The Great Game” that lasted for a century which was being played between the Russian & British Empires from 1807 to 1907, even though both had formal diplomatic relations, the swings of supremacy swayed to the one whose hard power would increase as compared to the other.

Coming to contemporary times, be it the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War & the Israel-Hamas War or the recently concluded India-Pakistan Conflict 2025, the 12-day Israel-Iran War & the military strikes between USA and Iran, the side which had to attacked, did so. For all talks of peace and prosperity & dialogue and diplomacy, there are 13 wars & conflicts going on as on date with over 37 million people killed in military confrontations since 1800.

This article does not aim to either discuss the reasons of any war and conflict, or who emerged victorious in the military confrontations. The fact simply remains that since mankind has existed on Earth, hard power has only mattered. But in this era, the existence of nuclear weapons puts the world in the most precarious situation, then what existed prior to World War II.

Even as the embers of the recent Israel-Iran War had not cooled, Mark Rutte, the NATO Secretary General alarmed the world on June 25, 2025 about the massive Chinese military buildup and potential for Taiwan invasion.

Last year, Admiral Samuel Paparo, the head of the US Indo-Pacific Command on October 28, 2024 stated that China is conducting the largest military buildup in world history. Early this year, on January 08, 2025 Air Chief Marshal AP Singh, the Indian Air Force Chief expressed concern over increased militarisation by China and the rapid pace at which the Chinese defence technology is growing.

Why would China continuously increase its military might when no country in the world can dare attack China? Clearly, China has military objectives to be achieved.

On January 17, 2024 Grant Shapps, the British Defence Secretary warned of multiple war theatres opening up in the next five years which would involve Russia, China, Iran and North Korea. How prophetic his words have turned out to be with the recently concluded Israel-Iran War and the US-Iran military strikes.

China’s war for Taiwan is only couple of years away. On March 17, 2025 General Upendra Dwivedi, the Chief of the Army Staff, Indian Army stated that two-front war on India is no longer a possibility, but a reality.

Any nation that has the remotest possibility of finding itself in a war, has to be fully prepared. For, there are no runners-up in a war. There is only a victor or a vanquished.

A nation’s military strength can thwart external threats and there can absolutely be no compromise on this issue. Any nation that goes against this well-established dictum will only face defeat.

While talks of dialogue, diplomacy and soft power look good on paper and are ideal photo-opportunities, in the time of a nation finding itself in a war or conflict, only hard power matters. Those same peaceniks who talk of global peace and reduction in a nation’s defence budget are the most vocal proponents of giving the enemy a befitting reply when their nation is attacked.

In the present times as the money power of nations/entities has increased, so has their military aspirations and scant regard for international rules and regulations. Hamas attacked Israel on October 07, 2023 to press for two-state solution despite the United Nations seized of the Palestine issue and vide Resolution 242 of 1967 having declared Israel’s occupation of the Gaza Strip and West Bank as illegal.

Israel attacked Iran on June 13, 2025 to destroy its infrastructure pivotal for developing nuclear weapons, though Israel itself is neither a member of the International Atomic Energy Commission nor a signatory of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and possesses 90 nuclear weapons. Russia attacked Ukraine on February 24, 2022 though there exists the Budapest Memorandum of 1994 in which Russia had pledged to respect Ukraine’s independence, sovereignty and existing borders.

Not to mention Pakistan’s occupation on Indian territories that lead to the Kargil War in May 1999, just three months after both the nations had signed the Lahore Declaration in February 1999 or the recent US attack on Iran just a day before the sixth round of talks were to held between Iran & USA.

Just few examples above have been mentioned where treaties, alliances, rules and regulations have been broken with impunity. The list is endless. The world is on an edge today. Every morning only brings news of turmoil and turbulence in some part of the world.

There can be no exceptions to any international rules and regulations. But it is happening blatantly. Those who have the hard power are doing it without any qualms while others are either suffering or rushing to the ineffective United Nations.

And neither can there be any justification for breaking the international order that exists in various forms, else there will be no sanctity left in talks and treaties. As it is, there is hardly any such respect left for those in vogue.

The United Nations has been rendered toothless due to the veto powers enjoyed by the P5 nations – USA, Russia, China, United Kingdom & France. It is indeed ironical that the United Nations which advocates democracy globally, doesn’t have democracy within its own organisation.

No wonder the world today is highly disenchanted with the United Nations as the P5 itself is divided into two camps. One, comprising the USA, France and the United Kingdom and the other Russia & China. And rarely in the United Nation’s 80-year-old history have the two camps ever agreed on any issues. What one camp supports, the other has to but, oppose.

Thus, any nation/entity having hard power and wishing to use it does so. For, it is aware that allegiance to any of the two camps will ensure no backlash. Mere statements or condemnation or passing of resolutions are certainly no deterrent for the nation/entity using hard power.

The world is now in the most dangerous phase ever as nine nations possess nuclear weapons and many others either in the process of acquiring them or already having acquired them clandestinely.

The after-effects of usage of a nuclear weapon need no deliberation. The nuclear weapons used in Hiroshima & Nagasaki in Japan in 1945 were of 15 kilotons yield each which resulted in 250,000 dead. The nuclear weapons of the present era have a yield of 100 kilotons and more, and the casualties that they can cause, will be in millions.

To avoid the any future wars/conflicts the international order has to be implemented effectively and the three superpowers ie USA, Russia & China have to step in and ensure fair and transparent implementation of international treaties and alliance by setting personal examples.

In any system or organisation if rules are broken and there is unfairness and partiality, there will be mayhem and chaos. In the global arena, the three superpowers have to neither break the international rules themselves nor over-look their close partners when they do so.

There is no ideal world but one can atleast try to attain idealism. Vince Lombardi’s quote has great depth “Perfection is not attainable, but if we chase perfection, we can catch excellence”. Today, it is free for all and anyone with hard power is using the way it deems fit with utter disregard to international rules and regulations. This is the root cause of the turmoil and turbulence that exists globally with mistrust and misgivings abnormally high, though nations are much richer than at the end of the World War II, educational levels are very high and borders are well defined, barring few cases.

Till international rules and regulations are followed, it is only hard power that will matter as it is already happening.

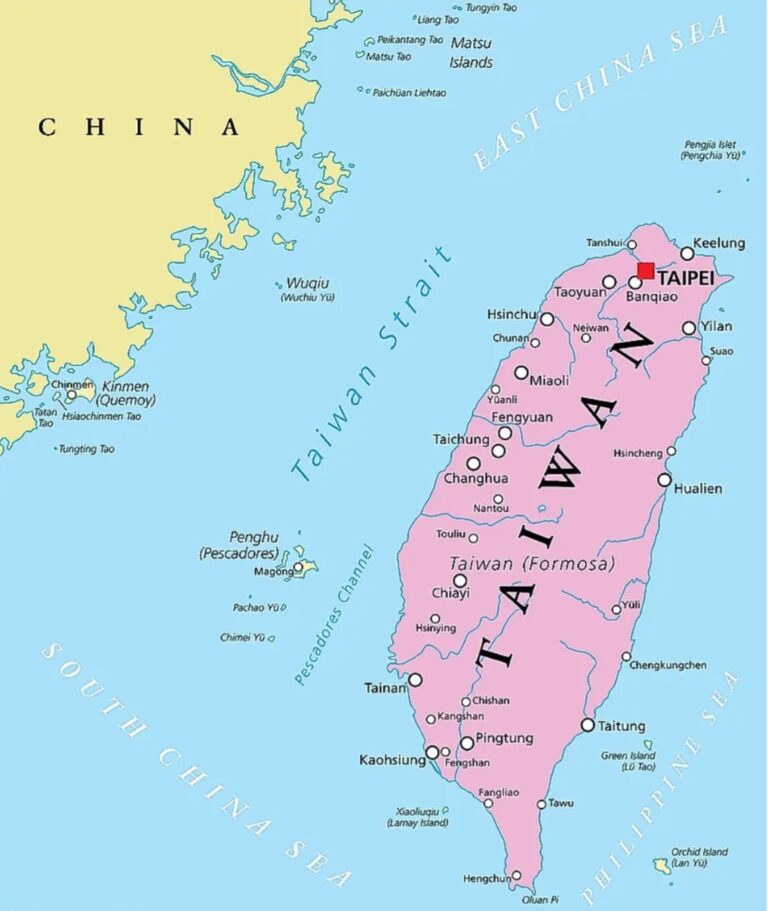

Taiwan at the Fault Line: Strategic Geography and the US-China Contest for Indo-Pacific Supremacy

By: Geehan Kooner

‘Wars begin where deep currents of conflict between major powers converge—where opposing military forces face each other, poised for action. One false move or a deliberate act can trigger disaster.’ One such flashpoint today is the sharpening dispute over Taiwan. The island has become the focus of tectonic scale geopolitical tensions, a faultline ready to fracture and pull China into a clash that could engulf the United States and its allies around the world.

The issue revolves around China’s claim over Taiwan, a self-governing democracy that functions like an independent nation but is not widely recognised as a sovereign state. Chinese President Xi Jinping, has tightened his authoritarian grip and built up a powerful military focused on what Beijing calls the “reunification” of Taiwan with the Chinese motherland. According to various reports, a full scale invasion could be launched by China by 2027. Latest Chinese military movements have only added to the seriousness. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has significantly raised its presence and activity around the island by sending dozens of warships, aircraft carriers, and warplanes. The growing antagonism over the Taiwanese Strait and the gravely entrenched US- China rivalry has made this conflict one of the most critical in the world.

Historical Fault Lines

To truly grasp and understand the present scenario, one has to step back and explore the past. China lost its grip over Taiwan during what is referred to as the century of humiliation. From the middle of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century, a series of invasions and internal disputes plagued China. To this day, this notion of humiliation has shaped the Chinese state ideology. In 1895, Japan seized control over Taiwan and made it a colony under the Treaty of Shimonoseki. However, after World War II, Japan was forced by the allies to surrender Taiwan. China, during that time found itself caught up and embroiled in a civil war with the Nationalists (ROC) led by Chiang Kai-shek battling against the Communists led by Mao Zedong.

In 1949, the People’s Republic of China was established on the mainland, when victorious communists marched into Beijing. After the government of the Republic of China was defeated, they retreated to Taiwan. Since that time, two rival governments have emerged, each claiming to represent China: the PRC in Beijing and the ROC in Taipei. The PRC government in Beijing sees Taiwan as a breakaway province and says there is only one China even though they have never actually governed it. Most of the world including the U.S. accepts this One China policy thus not recognising Taiwan as an independent country.

So, the question arises, ‘why is the U.S. backing Taiwan then?’ In the aftermath of the civil war, the US initially saw the nationalist government in Taiwan as the only legitimate or real China, turning it back and rejecting the communist government on the mainland. US soldiers were even stationed in Taiwan under a common defence pact. However, during the 1970s a major change occurred as the US moved closer to Beijing which resulted in the closing of the US embassy in Taiwan and pulling out the US troops. Despite the complexities, the US continued informal relations through the American institute in Taiwan which acts like a de facto American embassy. The U.S. deliberately follows an ambiguous and vague scheme on military support for Taiwan, aiming to balance deterring Chinese aggression while also managing Taiwanese aspirations for independence. Taiwan remains a critical flashpoint in the U.S.-China relations, with its status symbolizing deeper ideological and historical divisions.

Taiwan’s strategic geography and US “First Island Chain” Strategy

Taiwan’s location makes it a geopolitical flashpoint. Located merely 130 km away from China’s mainland, Taiwan is home to about 23 million people. The island is strategically positioned at the intersection of three crucial maritime chokepoints: the Taiwan Strait to the west, the Miyako Strait (between Taiwan and Japan) to the north, and the Bashi Channel (between Taiwan and the Philippines) to the south. These routes are essential for world trade, military logistics and regional security, making Taiwan a strategic barrier or gateway between the East China Sea and the broader Pacific Ocean.

Taiwan also sits at the heart of the US “First Island Chain” strategy. It is a line which links US allied territories and military bases running from Japan, South Korea and Philippines.

While Taiwan may not be an official ally of the US, its strategic and pivotal location plays an important role in allowing the US to project its power close to China’s coastline, safeguarding and protecting its allies and interests. On the flip side, the Chinese military finds it quite challenging to extend its reach beyond the first island chain making it tough for them to pose a direct threat or challenge to the United States and its interests in the indo pacific region.

To strengthen this island chain, the US is ramping up military cooperation and partnerships with Japan and the Philippines, which are also cautious about China’s expansionist ambitions. Nevertheless, Beijing is swiftly modernising its navy, in order to enhance its ability to be able to break through this network of US allies. Thus, it is the strategic location of Taiwan which makes it immensely important to both sides in order to gain an edge over the other in the region.

Taiwan’s Tech Edge

Besides its strategic location, the rivalry is also about money. Economically, the small island also has an outsize importance for both China and the US, and at the center of this economic clout is TSMC: Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. This company produces the world’s most advanced and sophisticated semiconductor chips making both the US and China dependent on them. These tiny chips are used in everything from smartphones and electric vehicles to advanced military systems and AI models. This technological centrality has made this small island indispensable to both the US and China. Any disruption or Chinese takeover could permanently shift economic tides against the US and it could lock the region into a new technological and economic order—one less open to Western trade and influence.

Taiwan’s Enduring Status Quo

Taiwan exists in a strange limbo, a situation that has existed for decades and shaped realities on the ground. Taiwan developed from a nationalist authoritarian regime into one of the strongest democracies in the region marked by competitive elections, free press, and progressive civil liberties. Taiwan was first in Asia to legalise same sex marriage. This ambiguous status neither fully independent nor under Beijing’s control has become the de facto reality. Last year a progressive party was re-elected for the third term, signaling to maintain this delicate balance.

Amid the ongoing rivalry between the US and China, many feel that Taiwan is only a pawn in this larger game. Regardless of external pressures, a strong sentiment runs across Taiwanese society that the island’s future should be decided by its people alone, through democratic means and without coercion. The island’s status remains unresolved but its democratic identity is firmly established.

Big Stakes for A Small Island

Taiwan represents ideological, historical, and strategic significance for both superpowers. It has embraced the US worldview, which promotes democracy and capitalism. China, on the other hand, is a one-party system with a socialist market economy. A significant Chinese narrative revolves around Taiwanese islands. Xi Jinping, the Chinese president views the reunification of Taiwan as an important step in addressing the aforementioned historical humiliation. This effort is a part of what’s known as ‘national rejuvenation’, aiming to make the Chinese nation a great power. For the US, supporting Taiwan also means keeping up key alliances in the region and promoting democratic ideals. If China invades and annexes Taiwan, we would witness democracy being snuffed out which could send chilling effects to democracies around the world. We would have questions being raised in South Korea, Japan and the Philippines on whether they can trust the United States for their security.

Given Taiwan’s strategic location and its symbolic worth, neither China nor the US can afford to back down, leaving the rest of the world as mere spectators in this unfolding superpower rivalry.

Pakistan’s Marriages of Convenience

By: Brigadier Anil John Alfred Pereira, SM (Retd)

As the geopolitical sands shift, India’s commitment must be to nurture the belief that true security and stature are earned, not gifted.

On May 10, 2025, just 88 hours after India launched Operation Sindoor, Pakistan stood battered militarily, humiliated diplomatically, and economically cornered. Precision Indian strikes damaged forward air bases, destroyed key terrorist infrastructure deep inside Pakistan, and exposed glaring failures in Chinese supplied radars and early warning systems. Public morale sank as the military brass scrambled to contain the fallout, painfully aware that their “iron brother” China had offered no overt support when it was needed most. Desperate to stave off collapse, Islamabad turned back to an old patron the United States.

American Lifeline

The United States stepped in with President Trump personally announcing the ceasefire to the world. Emergency packages from the IMF and World Bank stabilised Pakistan’s teetering economy and prevented default. Washington also fast-tracked the long-stalled F-16 upgrade and maintenance programme, shoring up Pakistan’s air combat readiness despite heavy losses. In a symbolic show of renewed favour, Pakistan’s Army Chief, Asim Munir, was elevated to Field Marshal. He was then welcomed to Washington for high-level talks with the US President signalling to the world that once again, America would not let Pakistan fail.

A History of Patronage

This rekindled embrace is hardly new. Post-independence in 1947, Pakistan quickly positioned itself as America’s frontline ally against Soviet expansion, receiving billions in military aid, modern weaponry, and economic support that propped up its fragile economy and emboldened its wars against India in 1965 and 1971. Washington’s patronage fuelled Pakistan military’s obsession with strategic parity with India and cemented a dependency that made the US a pillar of Islamabad’s regional leverage until trust ruptured dramatically after 9/11 when Osama bin Laden was found sheltered in Abbottabad under Pakistan’s protection.

‘Iron Brother’ Steps In

Disgraced in the eyes of the West, Pakistan pivoted to China, cultivating an ‘all-weather friendship’ romanticised as “higher than the mountains, deeper than the sea.” This was more than rhetoric with Beijing investing over US$ 60 billion through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), transforming roads, railways, ports like Gwadar, and vital energy infrastructure. China became Pakistan’s largest arms supplier, providing nearly 80% of its modern weapon systems and steady diplomatic support in global forums. For two decades, China’s loans and largesse underwrote Pakistan’s economy and reinforced its leverage against India, filling the vacuum left by a wary West.

Operation Sindoor Exposes Cracks in Sino-Pak Nexus

However, Operation Sindoor starkly revealed the limits of this ‘iron brotherhood’. As Indian jets struck deep and airbases were damaged, Beijing offered no intervention, leaving Islamabad to fend for itself. This betrayal forced Pakistan back into America’s arms, highlighting an uncomfortable truth in Pakistan’s eyes, allies may change, but national survival demands constant courtship of stronger powers.

Impact on India

For India, Washington’s swift rescue of Pakistan, reopened old wounds. The supposedly US brokered ceasefire, financial bailouts, and revival of Pakistan’s F-16 fleet are seen in New Delhi as undermining of India’s gains and a validation of Pakistan’s disruptive tactics. Meanwhile, India’s deep defence and energy ties with Russia, refusal to commit to American F-16 and F-35 jets, and repeated delays in critical US supplies such as the GE-414 engines for India’s indigenous fighter project, Apache helicopters, MQ9 drones etc have compounded frustrations. Many in India now question whether Washington truly prioritises India’s security interests over Pakistan.

India’s immediate neighbourhood is also turning into a chessboard for Chinese and American influence. China is tightening its grip on Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and the Maldives through loans, mega projects, and diplomatic cover often targeting regimes weary of India’s might. The US, eager to check Beijing’s Belt and Road footprint, has stepped up its own outreach with aid, training, and security pacts. This double courtship has emboldened smaller neighbours to play both sides, fuelling subtle anti-India sentiment and eroding India’s natural regional leadership

India’s Road Ahead: Self-Reliance and Strategic Maturity

In an age of shifting alliances and great power rivalries, India’s clearest lesson is this that there are no permanent friends or enemies, only enduring national interests. To thrive securely, India must double down on indigenous defence production, strengthen economic resilience, and diversify critical supply chains. Diplomatic agility will be key to deepening trusted partnerships while preserving strategic autonomy to avoid becoming a pawn in someone else’s game. Equally vital is restoring neighbourhood goodwill through connectivity, fair economic ties, and respectful diplomacy to outcompete China’s chequebook and America’s overtures. India must also harden its cyber frontiers, invest in technological innovation, and build robust information warfare capabilities to protect its narrative space.

Security Earned, Not Gifted

As the sands of geopolitics shift once more, India must remember that true security and global stature as Viksit Bharat are built from within by nurturing self-belief, investing in capability and capacity, and putting national interests above fleeting friendships. Only then can India stand steady in an uncertain world, secure in the knowledge that its destiny is determined at home, not dictated abroad. As the geopolitical sands shift, India’s commitment must be to itself first nurturing the belief that true security and stature are earned, not gifted.

G7 Summit 2025

By: Sonalika Singh, Research Analyst, GSDN

The G7 is an informal bloc of industrialized democracies, the United States, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom, that meets annually to discuss pressing global issues such as economic governance, international security, and, more recently, artificial intelligence (AI). Originally originated in 1975, when the United States, France, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and West Germany formed the Group of Six to coordinate their response to economic turmoil, including inflation and a recession caused by the OPEC oil embargo. Canada joined in 1976, and Cold War politics soon became part of the group’s agenda.

The European Union has participated fully in G7 meetings since 1981 as a “nonremunerated” member, represented by the presidents of the European Council and the European Commission. While there are no formal membership criteria, all G7 members are high-income democracies. As of 2025, the combined GDP of the G7 countries (excluding the EU) were approximately 44% of global nominal GDP and approximately 10% of the world’s population.

Unlike organizations such as the United Nations or NATO, the G7 is not a formal institution. It lacks a charter and a permanent secretariat. The rotating presidency sets each year’s agenda and manages summit logistics. Policy development is coordinated in advance through meetings of ministers and envoys known as sherpas. Nonmember countries are sometimes invited to attend.

The G7’s future has faced growing challenges, particularly due to tensions with Russia, formerly a member from 1998 until its suspension in 2014 following the annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region and increasingly with China. Internal disagreements over trade and climate policies have also tested the group’s cohesion. Nonetheless, shared concerns about Moscow and Beijing have fostered renewed unity. In a sign of closer cooperation, the G7 has coordinated sanctions against Russia in response to its war in Ukraine and launched a major global infrastructure investment initiative to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Russia joined the G7 in 1998, transforming it into the G8. Then U.S. President Bill Clinton believed that membership would grant Russia international legitimacy and encourage its post-Soviet leader, Boris Yeltsin, to align more closely with Western democracies. Clinton also hoped it would ease Russia’s concerns over NATO’s expansion into Eastern Europe.

However, the move sparked concerns particularly among finance ministries due to Russia’s weak economy and high public debt. Over time, Russia’s drift toward authoritarianism under President Vladimir Putin led to growing tensions with G7 members. The turning point came in 2014, when Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimea region. In response, it was indefinitely suspended from the group. Relations further deteriorated over Russia’s support for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad especially after chemical attacks attributed to Assad’s forces and over interference in U.S. and European elections.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 significantly deepened its international isolation, prompting the G7 countries to impose unprecedented sanctions, including phasing out imports of Russian oil and gas, barring Russian banks from transacting in U.S. dollars and euros, and implementing export controls aimed at weakening Russia’s military capabilities.

Additionally, G7 members have provided substantial financial and military support to Ukraine, collectively contributing hundreds of billions of dollars. In 2025, they also agreed to loan Ukraine $50 billion, using windfall profits from frozen Russian assets as collateral.

The 51st G7 Summit the group’s 57th annual meeting was held from June 15 to 17, 2025, in Kananaskis, Alberta, Canada. It was the second summit hosted in Kananaskis since the 28th G8 Summit in 2002 and the seventh overall to be held in Canada. Canada previously hosted six G7 summits and joined the group in 1976, alongside France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, to coordinate responses to global economic and political crises. The European Union was invited to participate starting in 1977.

Canada assumed the presidency of the G7 for the seventh time on January 1, 2025, and is hosting the G7 Leaders’ Summit in Kananaskis, Alberta, from June 15 to 17, 2025. This high-level event provides an opportunity for G7 member countries and invited guests to discuss some of the world’s most urgent challenges, including international peace and security, global economic stability, and the ongoing digital transition. Canada’s presidency is centered around three main priorities: protecting communities both at home and abroad, building energy security while accelerating the digital transition, and securing long-term, future-focused partnerships.

The G7 is a consensus-based grouping that operates without a formal treaty or permanent secretariat. The G7 presidency rotates annually among the seven member countries in the following order: France, the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, Italy, and Canada, with the European Union participating fully but not holding the rotating presidency. Each year, the presiding country sets the G7’s priorities and organizes the Leaders’ Summit, as well as ministerial meetings and related events. The number and type of these ministerial meetings are determined by the host country, and they typically conclude with joint communiqués or action plans. Although the annual summit and ministerial meetings are the most prominent events, the G7 operates continuously throughout the year. Leaders and ministers often convene additional meetings in response to urgent global crises, while expert groups and working-level officials meet regularly to implement commitments made at the high-level meetings.

Independent, non-governmental stakeholder groups known as G7 engagement groups also contribute to the G7 process by submitting annual policy recommendations. These groups often organize their own summits in the months leading up to the G7 Leaders’ Summit. The engagement groups represent various sectors of society, including business, civil society, labor, science, think tanks, women, and youth.

Mark Carney chaired the 51st G7 summit. The 2025 summit marked the first such meetings for European Council President António Costa, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, and German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, and it was the first G7 summit for U.S. President Donald Trump since the 45th meeting in 2019. It was also the first visit to Canada for Prime Ministers Starmer, Ishiba, Chancellor Merz, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, and South Korean President Lee Jae‑myung, while President Trump made his second visit since the 44th G7 summit in 2018.

Meanwhile, French President Emmanuel Macron and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy were attending Canada for the third time. In May, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum was invited and later confirmed that attending remained “a possibility,” and on May 30 Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva received an invitation and was expected to attend. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia was invited in June but ultimately declined to participate. Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto initially accepted an invitation from Prime Minister Carney but announced on June 12 that he would skip the summit to meet Singaporean Prime Minister Lawrence Wong and Russian President Vladimir Putin instead.

The core G7 members at the summit included host Prime Minister Mark Carney of Canada, President Emmanuel Macron of France, Chancellor Friedrich Merz of Germany, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni of Italy, Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba of Japan, Prime Minister Keir Starmer of the United Kingdom, President Donald Trump of the United States, European Council President António Costa, and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. Invited leaders included Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, Brazilian President Lula da Silva, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, South Korean President Lee Jae‑myung, and Ukrainian President Zelenskyy. Representatives from NATO, the United Nations, and the World Bank, Mark Rutte, António Guterres, and Ajay Banga, respectively also attended.

Although not a formal member of the G7, India is increasingly recognized as a powerful and influential global player. Since 2003, India has been regularly invited to participate in G7 Summits as an outreach partner, reflecting its rising economic and geopolitical importance.India has attended outreach sessions at the G7 Summit more than eleven times and has received invitations every year since 2019. This consistent engagement highlights India’s position as the world’s fifth-largest economy and a leading voice for the Global South on critical global issues such as climate change, energy security, and sustainable economic development.

The Canadian Prime Minister’s Office released an event schedule noting that the Foreign Ministers’ Meeting took place in Charlevoix, Quebec, from March 12 to 14, 2025, the Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ gathering was held in Banff, Alberta, from May 20 to 22, 2025, and the Leaders’ Summit occurred in Kananaskis Village, Alberta, from June 15 to 17, 2025. During the Charlevoix meeting on March 13, the G7 foreign ministers reached agreements on Ukraine’s long-term prosperity and security, regional stability in the Middle East, enhanced security in the Indo-Pacific, resilience-building in Haiti and Venezuela, support for peace in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and reinforcing sanctions while combating hybrid warfare and sabotage.

On June 14, Prime Minister Carney and Prime Minister Starmer met in Ottawa, where Starmer remarked en route that “Canada is an independent, sovereign country and a much‑valued member of the Commonwealth” in response to President Trump’s joking threats to annex Canada as the 51st state. That evening, the two leaders dined at Rideau Cottage and watched an NHL game between the Edmonton Oilers and the Florida Panthers. They agreed to establish an Economic and Trade Working Group, deepen the Trade Continuity Agreement, and Carney pledged that Canada would ratify the UK’s accession to the CPTPP. This meeting also marked the first conversation between the two leaders since Israel’s strikes on Iran, which had sparked a diplomatic push led by Starmer aimed at de‑escalating the Middle East crisis.

President Trump met with Chancellor Merz on June 16 but later stated he needed to leave early to manage the U.S. response to the Iran–Israel war, leading him to skip some scheduled meetings. On that same day, G7 leaders issued a joint statement affirming that “Israel has a right to defend itself,” reiterating their support for Israel’s security, and declaring that they regard Iran as “the principal source of regional instability and terror.”

Member nations announced several key outcomes and initiatives, one of the major agreements was the adoption of the Kananaskis Wildfire Charter, which aligns with the commitments outlined in the 2021 Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use to halt and reverse global deforestation and land degradation by 2030. The Charter was notably endorsed by India.

The G7 also launched the Critical Minerals Action Plan, building upon the Five-Point Plan for Critical Minerals Security established during Japan’s G7 Presidency in 2023. India likewise endorsed this new plan, reflecting growing cooperation on resource security beyond the G7. In addition, G7 leaders committed to strengthening the World Bank-led Resilient and Inclusive Supply Chain Enhancement (RISE) Partnership, aiming to bolster global supply chain resilience through coordinated investment and collaboration.

The summit included a strong condemnation of transnational repression (TNR), defined as efforts by states or their proxies to intimidate, harass, harm, or coerce individuals and communities outside their national borders. Leaders emphasized that such actions represent a form of foreign interference and must be countered collectively. The G7 also reaffirmed its commitment to prevent and counter migrant smuggling, through the G7 Coalition to Prevent and Counter the Smuggling of Migrants and the 2024 G7 Action Plan addressing this global challenge.

As the 2025 G7 President, Canada launched the G7 GovAI Grand Challenge and announced the creation of a series of “Rapid Solution Labs” aimed at developing innovative, scalable solutions to support the adoption of artificial intelligence in the public sector.Finally, the G7 pledged to work toward closing the global digital divide, aligning their efforts with the objectives of the United Nations Global Digital Compact, and reaffirming their commitment to equitable digital transformation worldwide.

The G7 Summit serves as a vital platform for India to strengthen diplomatic relations, advocate for the interests of the Global South, and contribute to shaping global economic, security, and technological policies. The next milestone,the 52nd G7 Summit, scheduled for June 2026 in Évian-les-Bains, France will test whether this cautious rebuilding of consensus can lead to sustained, long-term cooperation.

“In Kananaskis, Canada’s Presidency showed that we’re ready to create new international partnerships, deepen alliances, and lead member nations into a new era of global co-operation. Canada has the resources the world wants and the values to which others aspire. Canada is meeting this moment with purpose and strength” stated The Rt. Hon. Mark Carney, Prime Minister of Canada.

Why Turkey Supports Pakistan Militarily: A Strategic Brotherhood in a Changing World

By: Drishti Gupta, Research Analyst, GSDN

In today’s changing world, the strong military partnership between Turkey and Pakistan stands out as a key relationship between two major Muslim nations. While both countries share cultural and religious ties, their military cooperation goes beyond that. It is shaped by history, shared goals, and the need to respond to regional and global challenges together.

This article explains why Turkey supports Pakistan militarily by looking at their historical connections, strategic interests, political systems, and growing defense cooperation.

A History of Military Ties

The friendship between Turkey and Pakistan began soon after Pakistan became independent in 1947. In 1955, both countries joined the Baghdad Pact, later known as CENTO, along with other U.S.-allied countries. This marked the beginning of their military relationship based on collective security during the Cold War.

Turkey helped Pakistan gain access to Western military aid in the 1950s. One study from that period highlights how Turkey supported a broader defense partnership with Pakistan and other Muslim nations in the region.

Since then, Turkey has supported Pakistan during major conflicts with India, and Pakistan has backed Turkey on issues such as Northern Cyprus. This mutual support shows how military cooperation also reflects political solidarity.

Similar Military and Political Backgrounds

Turkey and Pakistan both have a history of strong military influence in their politics. In both countries, the armed forces have played leading roles in shaping national policy, often stepping in during political crises. Scholars point out that in both countries, the military has seen itself as a protector of national identity secularism in Turkey, and Islamic nationalism in Pakistan.

Because their military institutions have similar roles, this makes it easier for both countries to cooperate, exchange training, and understand each other’s defense strategies.

Defense Production and Technology Sharing

In recent years, Turkey and Pakistan have taken big steps toward working together on defense production and military modernization:

- Naval Projects: Pakistan signed a US$ 1.5 billion deal with Turkey in 2018 to buy four MILGEM-class warships. These ships are being partly built in Karachi, showing Turkey’s willingness to share military technology.

- Helicopters and Drones: Pakistan agreed to buy Turkish-made T129 ATAK helicopters, and both sides have shown interest in joint drone production, especially Turkey’s well-known Bayraktar TB2 drones.

- Training and Exercises: Turkish military schools train Pakistani officers, and the two armies often hold joint drills such as the “Ataturk” exercises.

These actions show a high level of trust and commitment. Pakistan normally only works this closely on military technology with countries like China.

Religious and Cultural Bonds

Religion and shared cultural values also play a role. Both countries see each other as part of the wider Muslim Ummah (community). Turkey openly supports Pakistan on the Kashmir issue, while Pakistan supports Turkey’s position on Cyprus and its internal security matters. This mutual respect and Islamic brotherhood help strengthen their military alliance. As one Turkish analyst put it, “Turkey is our friend and a brother Muslim country,” which makes its support more trustworthy to Pakistanis.

Countering Regional Rivals

One reason for closer defense ties is that both countries face strong regional rivals. Pakistan sees India as its main competitor, while Turkey has tense relations with Greece, Cyprus, and sometimes Israel. By working together, Turkey and Pakistan can balance the influence of these other powers. For example, Turkish drones and ships give Pakistan better tools to defend its borders and sea routes. In return, Turkey benefits from Pakistan’s military experience and regional connections.

A Changing World Order

The world is moving away from U.S.-led global dominance toward a multipolar system, where regional powers like China, Russia, and India are rising. Both Turkey and Pakistan are adjusting to this shift.

- Turkey, once closely aligned with NATO and the U.S., has moved toward a more independent foreign policy. Its military cooperation with Russia, and its growing role in regional conflicts, shows this change.

- Pakistan, similarly, has moved away from relying on U.S. support and is now more deeply engaged with China, Russia, and Central Asian countries through platforms like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).

This shift makes it natural for both countries to build stronger defense ties outside Western alliances. As one study notes, military cooperation between Turkey and Pakistan helps them protect their national interests in a world where the West no longer dominates global politics.

Strategic Significance of Pakistan’s Nuclear Status

Turkey is not a nuclear power, but Pakistan is. Some experts wonder if Turkey sees its relationship with Pakistan to learn from its nuclear experience or at least benefit from its strategic position.

Although no official nuclear cooperation has been reported, their military closeness raises questions about whether deeper defense collaboration could eventually include such discussions especially as Turkey invests more in missile and drone technology.

Political Leadership and National Identity

Domestic politics also play a role in the military relationship. Both Turkey and Pakistan are led by governments that promote strong nationalist narratives, often centered around military strength and independence.

Leaders in both countries such as President Erdoğan in Turkey and the military-backed leadership in Pakistan support stronger military cooperation as part of a broader nationalist and Islamic vision. Their messages focus on self-reliance, strong defense, and Islamic values, which appeal to large sections of their populations. Joint defense projects, especially with Muslim allies, help strengthen this image.

At home, both countries also face internal security threats, like terrorism and insurgency. Sharing counterinsurgency strategies and training makes practical sense.

Conclusion: A Growing Strategic Brotherhood

Turkey’s military support for Pakistan is not just about selling weapons. It’s part of a deep, long-term partnership based on shared history, similar political systems, Islamic solidarity, and common strategic interests. As the global order changes, both countries are working to protect their regional positions and reduce their dependence on Western alliances. Their growing military cooperation reflects these goals.

However, challenges remain. Turkey’s ties with NATO are uncertain, and Pakistan’s economic problems could affect future defense deals. Also, strong military influence in both countries can raise concerns about democracy and civilian control.

Still, the military relationship between Turkey and Pakistan is likely to grow stronger in the coming years. It stands as a powerful example of how two nations with shared values and goals can build a lasting strategic partnership.

They never Had the Chance: And We are Throwing ours Away

By: Ananya Das, Associate Editor, GSDN

The date was June 07, 2025. I don’t know what cracked open inside me today, but I can’t put it back. And I don’t want to.

It’s strange how we walk through life with working legs and closed eyes. I’ve had better days than today, more eventful, glitterier. But not one of them made me feel this loud inside. Not one made me this aware of the silence I had been swallowing for years. I’ve never had this kind of urge to post online before, not because I didn’t want to, but because I didn’t think I had something real to say.

There was this book, just lying there in my shelf like a ghost of responsibility I never claimed. For years. I’d walk past it, feel a little guilty maybe, and forget again. Today, I don’t know what god or demon twisted my gut, but I picked it up and started reading. And then I had to stop. The words weren’t just ink anymore. They were truth bullets. They got under my skin. They forced me to bleed.

We’re taught the same damn moral line since childhood — “Respect everyone equally.” What a joke. Schools shove it down our throats, parents pretend to live by it, and then we all grow up and become the kind of people who don’t even look at a waiter’s face while accepting service. You think saying “thank you” without eye contact makes you a decent person? You think handing someone a tip without treating them like a human being makes it okay? That book described it. The quiet violence of being treated like a tool. Security guards, waiters, nail artists, people who feel dehumanized every single day by the very people who pretend they “respect everyone.” And it’s true. It’s all true. We’re not humans, we’re walking scripts. Robots trying to remember how to sound polite while actively ignoring souls.

Even the teachers preaching these things in class aren’t exempt. Most of them are just saying words like empty envelopes. They don’t even believe what they’re teaching. They want their salary, their off-time, their life back. And we just eat it up, recite the same values, and become part of the same disease.

That hit me like a truck today.

And then, as if the universe wasn’t done dragging me through the mud, another thought slammed into my chest: what about those who can’t even read this book? What about those who don’t speak English? What about those who’ll never access this pain, this clarity, because privilege never kissed their doorstep?

And even for people like me, people who can read, who do have access – we let things rot. I had that book for years. Just lying there. Like most of us do with our potential. We ignore it. Because we can. Because nothing forces us to care until something inside us is dead enough to finally notice the funeral.

Later today, in the evening, my brain said, “Let’s watch a film.” No reason. Just… because I can. And that sentence alone made me flinch. The privilege in that. I have had a Netflix subscription for over two years. The film I chose? “Mona Lisa Smile.” My friend recommended it to me five years ago. I didn’t watch it. I wasn’t interested. I was busy being empty.

But today I did. And it gutted me. Because it tied everything together, that book, that thought, this generation, this broken system we pretend to thrive in. It all came full circle. That film screamed what I was already hearing in my head.

I realized I’ve had the platform all along. I’ve had the language. I’ve had the space. I’ve had this blog sitting here like an open mouth, waiting for me to say something real. For months, my to-do lists have said: “Write the blog. Write the goddamn blog.” And I didn’t. Not once. I had all the time, outside work. I had words boiling in my throat. But I didn’t write.

Why?

Because I was too damn used to wasting myself.

Even my Latin classes. I started like a star. The outperformer. The overachiever. And then? Flatline. I kept showing up like a shell of that version. I told myself it’s okay to be normal. But it’s not. Not when you know you’re meant to be more. Not when you’ve tasted more.

Today I killed that version of me. The one that made peace with shrinking.

And it made me see just how lucky we are. We, who get to speak. Who get to write. Who gets to read in languages that others never got the chance to learn. We are living in an age where women can share their minds, where broken people can scream into the internet and someone, somewhere, will listen. We are living the dreams of those who died screaming into pillows. And still, we scroll. We numb. We wait for some “right moment” that never arrives.

This era isn’t perfect. People are cruel. The world is unkind. But you know what else is true?

If you ask for help, you’ll get it. If your pain is honest, someone will hear it. If your voice is real, someone will read it. But you have to use it. You have to stop wasting your one damn chance at being heard.

So here I am. Writing what I should have written months ago. Screaming what I should’ve said out loud. Because I finally remembered that no one was holding me back. It was me.

Use your privilege. Use your voice. Use your time.

Because somewhere, someone died without ever having the chance.

And you?

You’re alive.

So, act like it.