By: Sonalika Singh, Consulting Editor, GSDN

In mid-January 2026, the Trump administration formally advanced its Gaza peace initiative from an initial ceasefire phase to a far more ambitious second phase centered on demilitarization, technocratic governance, and reconstruction. In a White House statement issued on January 16, President Donald Trump presented a complex institutional architecture intended to guide Gaza’s transition from war to post-conflict recovery. At its core was the establishment of a new international body the Board of Peace alongside Palestinian technocratic institutions and an international stabilization force.

The initiative represents one of the most sweeping attempts by any U.S. administration to reengineer post-war governance in Gaza. It combines security guarantees, international oversight, economic reconstruction, and a vague but consequential political horizon for Palestinians. Yet while the architecture is expansive, many of its foundations remain uncertain. As Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu noted after the announcement, much of what has been unveiled so far is “declarative”: symbolically significant, but not yet transformative on the ground.

Whether Trump’s Board of Peace succeeds will depend not on its pageantry or ambition, but on how it addresses the deeply entrenched dilemmas that have long undermined Gaza’s stabilization: security vacuums, legitimacy deficits, governance fragmentation, funding shortfalls, and the absence of a credible political endgame.

President Trump first announced his 20-point Gaza peace plan on September 29, 2025, alongside Netanyahu at the White House. The plan called for an immediate ceasefire, the release of Israeli hostages held by Hamas, humanitarian access to Gaza, and the withdrawal of Israeli forces to pre-agreed lines. Within days, Israel and Hamas agreed to implement the first phase, bringing an end to nearly two years of devastating war.

The early success of the ceasefire lent credibility to the plan and created diplomatic momentum. On November 17, the U.N. Security Council adopted Trump’s proposal as the framework for Gaza’s postwar transition, lending it unprecedented international legitimacy. However, while the ceasefire addressed the war symptoms, it did not resolve its structural causes. The familiar “day after” questions resurfaced almost immediately: Who would govern Gaza? Who would provide security? How would Hamas be dismantled or integrated? And what political future, if any, awaited Palestinians?

The January 2026 announcements were designed to answer these questions. The administration unveiled a multilayered governance structure, including a National Committee for the Administration of Gaza (NCAG) composed of 15 Palestinian technocrats, a Gaza Executive Board integrating regional and international actors, and an International Stabilization Force (ISF) tasked with maintaining security and overseeing demilitarization. Above all stood the newly ratified Board of Peace, chaired indefinitely by President Trump and endorsed by dozens of states.

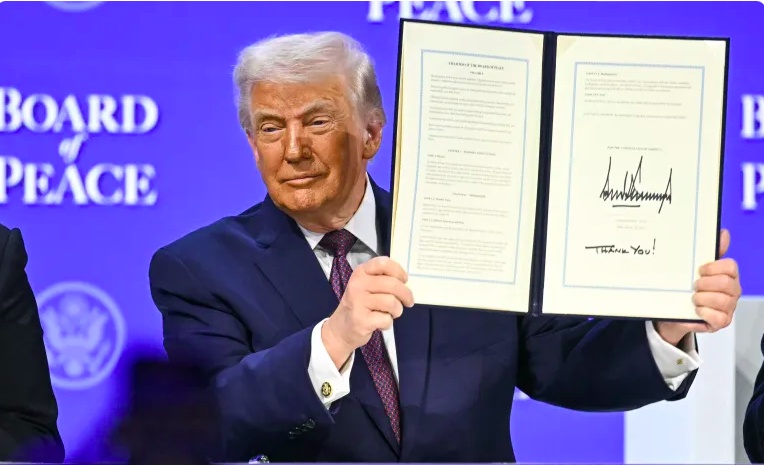

At a ceremony in Davos on January 22, Trump ratified the Board of Peace as an “official international organization.” Member states include Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Qatar, the UAE, Pakistan, and Indonesia, among others. Notably absent or uncommitted are several major European and Asian powers, including France, the United Kingdom, and Japan. Their hesitation reflects concerns that the Board is intended to bypass or even replace the United Nations.

Those concerns are not unfounded. The Board’s charter does not explicitly reference Gaza, suggesting a broader and loosely defined mandate. It lacks clear grounding in international law, formal enforcement mechanisms, or accountability structures. Power is highly centralized, with Trump positioned as lifetime chair and decision-making authority concentrated within a small executive circle closely tied to U.S. leadership.

While the Board is framed as a corrective to what Trump has described as a “broken” UN system, critics argue that it replicates many of the shortcomings it claims to address inefficiency, opacity, and politicization without offering genuine institutional innovation. Instead, it risks functioning as a personalized platform wrapped in the language of multilateralism.

At the heart of phase two is the transition from ceasefire to governance. The NCAG is intended to administer Gaza temporarily, restoring public services, rebuilding civil institutions, and stabilizing daily life. Its members are largely apolitical technocrats with prior experience in Palestinian institutions, civil society, or the private sector. None are current officials of the Palestinian Authority (PA), a concession to Israeli objections.

This technocratic approach is pragmatic, but it carries risks. Post-conflict governance is political. Decisions about land, security, justice, and reconstruction cannot be insulated from broader questions of legitimacy and representation. Without a clear timeline or pathway to elected Palestinian leadership, the NCAG risks being perceived as an externally imposed authority rather than a bridge to self-rule.

Equally contentious is the plan’s insistence that Hamas be excluded entirely from governance and disarmed permanently. The proposal offers amnesty and safe passage for militants who lay down arms, but provides little clarity on enforcement, verification, or incentives. Hamas has historically rejected disarmament absent a comprehensive Israeli withdrawal and a credible political horizon. Regional actors are divided on whether demilitarization can be achieved without reigniting conflict.

Security is the linchpin of the entire initiative. The proposed ISF is expected to fill the vacuum left by Hamas and the Israeli Defense Forces, maintain public order, facilitate humanitarian operations, oversee border management, and train Palestinian police forces. Yet critical details remain unresolved: the size of the force, contributing nations, command structure, rules of engagement, and exit criteria.

Peacekeeping missions in urban, post-conflict environments are notoriously difficult to sustain. Without local consent, the ISF risks being viewed as a continuation of occupation under a different name. Palestinian participation and ownership will therefore be essential, as will a clear mandate tied to an eventual handover to Palestinian self-policing.

Regional politics further complicates matters. While countries such as Indonesia, Pakistan, and Italy have expressed tentative openness to participation, others are wary of being drawn into an open-ended mission under Israeli oversight. Turkey, a potential bridge actor with ties to both Israel and Hamas, has been explicitly rejected by the Israeli government as a participant.

Gaza’s reconstruction will require tens of billions of dollars, years of sustained effort, and a functioning governance and security environment. Early recovery priorities include rubble clearance, restoration of water and electricity, reopening hospitals and schools, and emergency employment programs. These visible “peace dividends” are essential for stabilizing communities and building public confidence.

Medium and long-term reconstruction, however, will confront formidable obstacles destroyed infrastructure, disputed land records, frozen financial systems, and fragmented administrative authority. While Trump’s plan envisions “miracle cities” and special economic zones to attract investment, investors will require assurances of security, legal clarity, and political stability that do not yet exist.

Crucially, reconstruction cannot be reduced to technical exercise. It must be embedded within a broader political and institutional renewal that reconnects Gaza with the West Bank and integrates Palestinian governance into regional economic networks. Without this, reconstruction risks entrenching fragmentation rather than overcoming it.

Perhaps the most consequential weakness of the Board of Peace initiative is its ambiguity regarding the political horizon. The final points of Trump’s 20-point plan gesture toward Palestinian self-determination but avoid explicit reference to statehood. This vagueness may be tactically necessary to maintain Israeli cooperation, but it undermines the plan’s long-term credibility.

History suggests that transitional arrangements without a defined endpoint tend to ossify. Without a credible pathway toward elections, unified Palestinian governance, and negotiated final-status issues, transitional authorities risk becoming permanent placeholders. This, in turn, fuels cynicism, resistance, and instability.

A viable political horizon will require reconnecting Gaza and the West Bank under a unified Palestinian authority, supported by regional guarantees and international recognition. It will also require sustained engagement with Israeli political realities, which remain deeply resistant to Palestinian sovereignty.

What distinguishes this initiative from past efforts is the degree to which it is tied to a single individual. President Trump has placed his personal authority, reputation, and legacy at the center of the process. His ability to pressure allies, bypass bureaucratic inertia, and dominate diplomatic narratives may generate short-term momentum.

Yet personalization is also a vulnerability. Durable peace processes depend on institutions, not individuals. If Trump’s attention shifts, or if political calculations override long-term strategy, the entire architecture risks unraveling. Moreover, an institution built around one leader’s brand lacks the neutrality and continuity required to mediate deeply rooted conflicts.

The Board of Peace reflects a genuine frustration with the failures of existing diplomatic frameworks. It identifies real problems of fragmented governance, ineffective multilateralism, and the absence of enforceable commitments. In doing so, it captures a moment of opportunity created by the Gaza to ceasefire and unprecedented international engagement.

Yet ambition alone does not guarantee success. Without clear mandates, dispersed authority, Palestinian legitimacy, sustainable security arrangements, and a credible political horizon, the Board risks becoming another well-branded but hollow initiative. Peace cannot be imposed through spectacle or centralized power. It is forged through inclusive institutions, enforceable rules, and sustained, often unglamorous work.

If treated as one tool among many embedded within international law and coordinated with existing institutions, the Board of Peace may add marginal value. If advanced as a substitute for the global system it seeks to replace, it is likely to fail.

Ultimately, Gaza’s future will not be decided in Davos or Washington alone. It will be shaped on the ground, by Palestinians rebuilding their lives, by Israelis recalibrating their security assumptions, and by regional and international actors willing to invest not just resources, but patience, legitimacy, and shared responsibility. No board, however, grandly announced, can shortcut that reality.

About the Author

Sonalika Singh began her journey as a UPSC aspirant and has since transitioned into a full-time professional working with various organizations, including NCERT, in the governance and policy sector. She holds a Master’s degree in Political Science and, over the years, has developed a strong interest in international relations, security studies, and geopolitics. Alongside this, she has cultivated a deep passion for research, analysis, and writing. Her work reflects a sustained commitment to rigorous inquiry and making meaningful contributions to the field of public affairs.