By: C Shraddha

Collaboration was the cornerstone of the Chinese Space Programme in the initial days. The 1950s saw the People’s Republic of China (PRC) partnering with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) through a technology exchange programme. Towards the end of the decade, renowned scientists Zhao Jiuzhang and Qian Xuesen from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) proposed the need to advance Chinese involvement in the research and launch of indigenous satellites. As the Sino-Soviet alliance crumbled under divergent interpretations of communist ideologies, the independent efforts of China helped safeguard its space ambitions.

In 1958, the director-general of the CAS Institute of Geophysics, Zhao Jiuzhang, formed a group of scientists and engineers known as Group 581 to commence China’s satellite and space research programme. However, despite this initial feat, China lacked the industrial and material capabilities essential to boost its space programme. Conscious of the lack of research prowess in the field of upper atmosphere, magnetosphere, ionosphere and interplanetary physics, Zhao led efforts in creating the first space science research institute in China.

Despite the initial setback, by the 1960s, the country had acquired rudimentary knowledge in space sciences while obtaining semiconductor and launch vehicle capabilities. In order to exhibit its newfound competence, Zhao proposed to develop and launch China’s first man-made satellite. Thus, marking its name in the space race, on April 24, 1970, the country successfully launched the heaviest satellite of the time, Dong Fang Hong.

With the onset of the 21st century, China’s accomplishments in its space programme positioned it as one of the world’s leading space powers. In January 2019, China became the first country to successfully deliver a rover on the Moon’s far side, enabling the first close observation of the “dark side of the moon”. The Chang’e-4 mission with its landing platform and Yutu-2 rover made a soft landing on the Von Karman Crater in the South Pole-Aitken basin on the far side of the lunar surface after 26 days of take-off. This successful mission enabled scientists to delve deeper into the understanding of the Earth and the nascent solar systems. As per Chinese officials, after a thousand days on the dark side of the lunar surface, the Yutu-2 rover covered a total distance of 2,754 feet on the lunar surface while acquiring approximately 3,632.01 gigabytes of data.

While the world experienced an unprecedented pause due to the global pandemic in 2020, China was focused on continuing its pioneering missions. In 2020, China launched the first independent interplanetary mission to Mars, Tianwen-1, consisting of a trifecta- lander, rover and combination orbiter. Scientists believe that a successful Mars landing requires precise skills and execution, as the atmosphere of the planet requires rovers to have heat protection during descent. China’s ability to deliver such sophisticated and complex mechanisms on its first missions is a feat that sets it apart from other space powers. As Cornell University Aerospace Engineer Mason Peck rightfully commented, “A successful landing would put China among elite company”. According to the Tianwen-1 team, the intention of the mission encompassed a broad scientific agenda. But the main goal of the orbiter was to “map Mars’ morphology and geology while using a Mars-Orbiting Subsurface Exploration Radar instrument to measure soil characteristics and water-ice distribution.” Additionally, the rover would also acquire data on the ionosphere, gravitational and electromagnetic field, as well as communicate with Earth.

In the same year, China’s plans to progress in the domain of space-based broadband internet services came to light after the country submitted a filing with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) for “a constellation of nearly 13,000 satellites.” As per the state media house Xinhua, in 2024, the first group of satellites under the GuoWang mega-constellation or “national network” was launched along with the Long March-5B rocket and Yuanzheng-2 from the Wenchang spaceport. The project undertaken by the state-owned China Satellite Network Group Co Ltd was declared a success as the satellites “entered into their predetermined orbit.” Envisioned as a competitor to Elon Musk’s SpaceX Starlink, this Chinese mission focuses on supplying broadband services both domestically and internationally while fulfilling China’s security objectives.

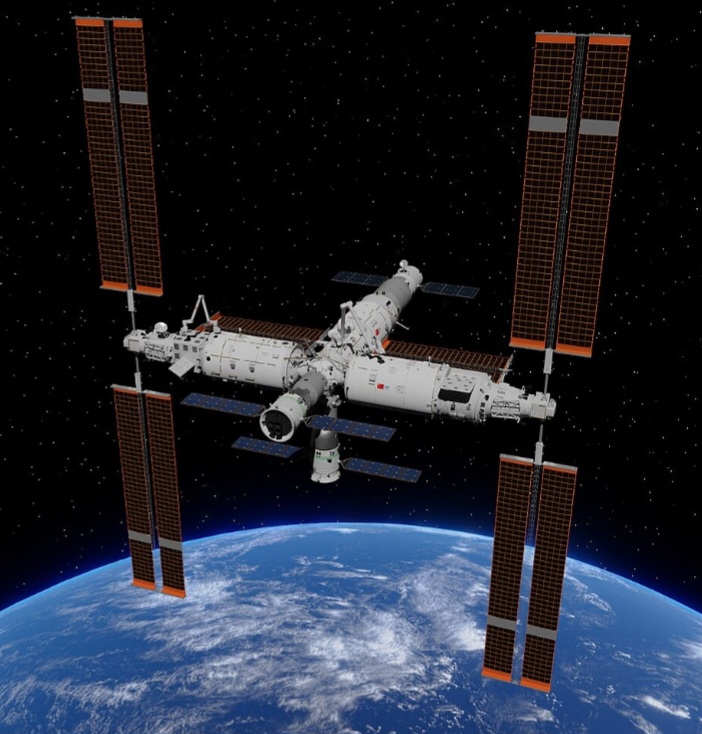

On November 29, 2022, the country launched the Shenzhou 15 mission from the Gobi Desert with three astronauts, who docked with the Chinese Space Station, Tiangong or heavenly palace, six hours later. Their mission marked the final stage in completing the space station’s construction. With this, China became the third country to operate a permanent space station after the United States and Russia. However, China’s independent effort in building and operating Tiangong sets it apart from the collaborative efforts of the other space powers. According to scholars, this feat marks the country’s effort to be self-reliant in an era where power dynamics influence space ambitions and vice versa. As per reports, Tiangong was designed to have its own propulsion, power, living quarters and life supporting systems while providing refuelling power to China’s newest telescope Xuntian. Additionally, the indigenous space station will allow the country to promote space research while bypassing the sanctions enforced by the US regarding the usage of the International Space Station.

Continuing its intention of rivalling SpaceX’s Starlink, the country launched a second group of satellites under the G60 constellation mission. Initially, eighteen satellites were launched into a preset orbit on Long March 6A rockets under the supervision of the state-backed Shanghai Spacecom Satellite Technology (SSST). Popularly known as the Spacesail, Qianfan or thousand sails, the project intends to launch over 10,000 low-orbit constellation satellites to enable international network coverage while pushing towards 6G connectivity. According to the Senior Vice-President of SSST, Lu Ben, the company has an ambitious goal of launching 648 satellites by 2025. Furthermore, they intend to accomplish the first phase of the G60 mission by 2027 with 1,296 satellites providing global coverage. “We plan to further enhance the constellation’s services by lowering the satellite orbit from over 1,000km to 300-500km, facilitating direct mobile connections and advanced IoT applications, with a goal of having over 15,000 satellites by 2030”, said Lu.

The year 2024 was a testament to China’s immense space capabilities. On October 15, 2024, the government released the Mid-to-Long Term Plan for Space Science Development, which laid out the country’s plans to dominate the international space arena by 2050. Co-authored by CAS, the Chinese National Space Administration and the China Manned Space Agency, the plan outlines seventeen focus areas and five scientific themes encompassing research on space-based gravitational wave detection, Sun-Earth connection, space weather observation and microgravity science. The development roadmap is strategically divided into three phases. Phase 1 consists of achieving pertinent scientific breakthroughs via “lunar and planetary exploration” by 2027. Phase 2 involves the development of a lunar research station and advancement in high-precision space observation by 2035. The final phase of the plan involves leading the international space programme through scientific breakthroughs and deep space missions.

In light of this comprehensive roadmap, China’s current scientific development in space sciences remains consistent and strategic. The Chang’e-6 space mission showcased the country’s determination to become a global space power. On May 3, 2024, the PRC launched Chang’e-6 from the Wenchang Space Launch Centre in Hainan with the aim of collecting samples from the far side of the lunar surface. Given the complexity of the mission, a successful retrieval of the samples would make China the first country to achieve such a feat. It ended its 53-day exploration on June 25, with the return module successfully landing in Inner Mongolia with samples of rock and soil collected from the South Pole-Aitken Basin, thus creating history.

The Deputy Chief designer of the mission, Wang Qiong, wrote, “After the lunar samples are delivered to the laboratory, we will first unseal the sample container, extract the samples, and separate the samples collected on the lunar surface from those drilled under the surface. A portion of the samples will be stored permanently, while another portion will be stored at a different location as backup in case of disasters. Then we will prepare the remaining portion, and distribute it to scientists in China and foreign countries in accordance with the lunar sample management regulations.” According to scientists, these samples will enable further research and enhance human understanding of lunar history.

The lunar efforts of China are unbound. In 2024, PRC scientists revealed plans to construct egg-shaped igloos on the lunar surface as part of colonisation efforts. Initially structured to withstand the unforgiving environment of the moon, subsequent designs would account for cosmic radiation and temperature fluctuations, as stated in reports. According to news reports, the structure would include designated working and living spaces, potentially built using 3D printing technology and robots. Using lunar soil samples collected from previous space missions, Chinese scientists are experimenting with brick-making techniques for future lunar settlements.

China’s development of space prowess is a testament to its growing influence in the international sphere. From its early dependence on Soviet assistance to being the first country to successfully collect samples from the dark side of the moon, Chinese innovation and infrastructure have developed beyond competition. The strategic and calculated missions undertaken by the country have helped position it as a major space power. The unveiling of the long-term roadmap to dominate the international space arena by 2050 further reiterates China’s commitment to sustained scientific advancement and strategic autonomy. Through milestones such as the Tiangong space station, the country is establishing itself as a space power opposite to the United States. As countries compete to dominate the space race, China’s ability to match or surpass US accomplishments showcases the former’s strategic foresight, technological advancements and rising potential in redefining global leadership in outer space.