By: Nandini Khandelwal, Research Analyst, GSDN

Recently, Italy backed out of the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also referred to as BRIXIT, i.e., Exit from BRI before the upcoming renewal of the agreement in March 2024. This is significant as Italy was the only G-7 country to be a part of it beginning in 2019, the largest-ever global infrastructure undertaking. Italy saw an opportunity to leverage its position, having suffered three recessions in a decade and growing scepticism towards the European Union. It was looking forward to attracting investments and increasing exports to the PRC’s huge market.

Italian Defence Minister Guido Crosetto remarked, “The choice to join the BRI/Silk Road was an improvised and wicked act, made by the Government of Giuseppe Conte which led to double negative result”.

Italy played a major role in the significance of the BRI as it refreshed the golden memory of China’s old Silk Road which connected Central Asia, West Asia and Europe. In addition, Italy is home to the largest population of the PRC in Europe, and deep shared trade links but most importantly, the PRC saw it as a gateway to influence Europe in its far-sighted future. However, it seems like this remains a dream since Italy has dumped the Dragon which has immense implications for the geo-politics.

Background

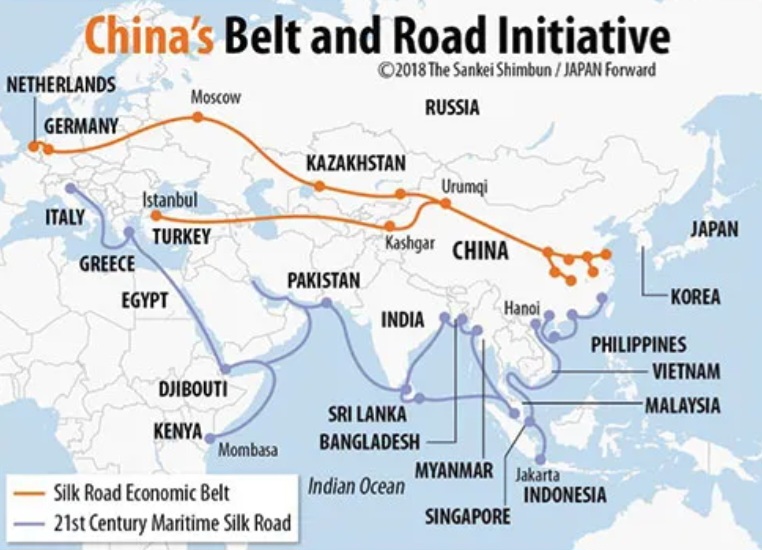

BRI is an infrastructural project of the PRC aspiring to connect to the world. It began with the 2013 Xi Jinping’s speech in Kazakhstan where he announced a new trade route based on the ancient Silk Road.

It is a colossal project that consists of at least 60% of the world’s population at present. As of August 2023, the number of countries that have joined the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) by signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with China (excluding Italy) is 148 including itself, spread across Sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia, East Asia and Pacific, Latin America and Caribbean, West Asia and North Africa (WANA) and South-East Asia.

It is referred to as an amorphous project due to its secrecy regarding the objective. For instance, it could mean building infrastructures for the members or upgrading them; providing loans and investment in the developing countries in need and providing overland routes. Interestingly, the term “road” in the project means the maritime Silk Road all across the world through building ports for the member countries, like Djibouti, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan etc.

Geopolitical analysts contend that the PRC strategically placed these ports as military bases in particular nations, close to the choke points, to reinforce its power in the region, popularly known as the “String of Pearls theory,” which conspired around India in order to eventually become a global hegemon. In addition to creating economic reliance on the nations, it also asserts geopolitical power to move around as it sees fit.

It is dubious because, unlike institutions located in the West like the IMF or World Bank, which offer economic assistance to nations subject to certain criteria, BRI does not impose any such requirements, giving the impression that it is a Ponzi scheme. Recent advances have produced these outcomes. For instance, after promising to assist Sri Lanka with its economic difficulties, China ended up leasing the country’s port of Hambantota from Sri Lanka for a period of 99 years. In the case of Djibouti, China actively contributed to the construction of its ports, railways, highways, and related infrastructure. In addition, China took over the country’s logistics support base on a ten-year lease in January 2016 and, interestingly, by mid-2017, had completely transformed the location into a base of operations for itself. This naturally draws attention to China’s “debt trap” tactic, which keeps control of these defenceless nations.

Xi Jinping’s paradox of cooperation through his wolf-warrior approach

Used as a buzzword word for Chinese diplomacy post the outbreak COVID-19 pandemic, Xi Jinping has been using it as a support base due to its popularity domestically as well as asserting its power aggressively at the international level, reflecting his call for the “fighting spirit”.

Chinese current diplomacy is a result of an evolution, beginning with Zhou Enlai, the founder, who stated “ability to hide its fist when needed behind velvet gloves”.

Deng Xiaoping in the early 1990s called for keeping a low profile, stating his popular statement “hiding brightness, biding our time”

Jiang Zemin (1993-2003), called for being more active. It was in his era that the PRC began asserting its power over the Mischief Reef (South China Sea) in the year 1995 while focussing on economic growth.

Hu Jintao’s (2003-13) era was of rapid economic growth for the PRC, portraying itself as a responsible state. However, the territorial disputes with Taiwan and in the South China Sea persisted. Notwithstanding, it began managing its relationship with the major economies of the world rather than forging foreign policy as a major power.

It only happened since Xi Jinping came to power and pushed for diplomacy that favoured the PRC’s major power status across the globe. However, there is a paradox in his style of diplomacy. While Chinese policy urges for “opposing sides or another cold war”, its unilateral and baseless assertion of power is creating a situation, compelling the countries to form alliances to counter it. For instance, the recent update in its map shows the 10-dash line in the South China Sea region, in addition to the 9-dashed line, ruled as having no legal basis by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague in 1947 and by the United Nations. The PRC’s cartographic aggression, one of the warfare tactics used by China besides psychological and controlled public opinion has been going on since then.

The liberal and egalitarian views of his diplomacy often contradict his realist actions. His conception of a shared future for all mankind was characterized by win-win cooperation in his UN speech of 2015 where he re-instated the idea of a “community of common destiny” as a continuation of his predecessor Hu Jintao. He furthered the idea by portraying the PRC as a responsible state, which thinks of other states’ interests rather than exclusively its own. He institutionalized this idea through practical forms of the BRI and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), envisioning the country to reach great rejuvenation by becoming a global leader.

Every nation considers its own national interests, but when those interests are pursued or controlled through unfair and illegal tactics, problems arise. For instance, the BRI is beneficial as long as it promotes increased interconnectedness through globalisation and serves as a tool for economic assistance and development. When it forces them into a geopolitical reliance and debt-trapping country, it turns into a wolf warrior policy. Coercive tactics like this are incompatible with liberal and egalitarian ideals. The hostile language used in the new major-country diplomacy is likely to vary across subject areas and to get worse when it comes to “core national interests.”

Path for India

The reality check that the members are getting from signing up with the PRC’s BRI provides India with an opportunity to make the world believe in its balanced leadership. The biggest example this year is the G-20 summit whose presidency is with India. The recent summit held in India proved its moto of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (One Earth, One Family, One Future) being successful in getting the member-states to consensus, amid the polarizing issue of Russia-Ukraine.

In fact, the summit’s ground-breaking announcement is a “new economic corridor connectivity” connecting Europe, West Asia, and India via ship-to-rail transit was made among participants, including the US, despite it having no part in the transit route. It is important to be specific because the PRC’s BRI model, which just took a hit from Italy, could be substituted by this corridor.

In addition, the PRC’s decision to skip the ASEAN and G-20 summits immediately following its aggressive cartography is indicative of a childish attitude. According to the speculation, it’s because of domestic pressures that Xi is experiencing as a result of the current economic slump in the nation. But the reality reveals the PRC’s “hegemonic, high-handed” mentality, which prevents it from being able to witness someone else assuming the reins, forcing it to watch from the sidelines.